Supply chain crisis a reminder of marketing’s forgotten priority – place

The world is in the middle of a supply chain crisis that is delaying shipments and clogging many ports. In his latest Promotion Fix column, Samuel Scott reminds us that ’place’ is an often-ignored part of the marketing mix and shows what marketers should do in both communications and distribution.

Place (or distribution) is the P in the marketing mix that marketers discuss the least. But the world’s ongoing supply chain troubles show that the industry should continue to ignore it at our own peril.

Why? The same problem that plagues marketing communications today is also harming distribution. More on that below.

The 4 Ps are levers that companies can use. The tech world aims to build the best products. New FMCG brands often have lower prices to undercut the competition. Many advertising executives want to focus on promotion.

But how did Netflix defeat Blockbuster in the early 2000s? By concentrating on distribution with a DVD-by-mail service. After all, the two had the same products, and Netflix could never outspend Blockbuster on ads. A new type of media distribution was the strategic source of leverage.

In 1999, Netflix sold a $16 monthly subscription plan in the US. People could have four DVDs out at a time without any late fees and just mail the watched movies in pre-paid envelopes at their leisure. The company’s insight was that customers hated late fees but could not always return videos on time.

But the marketing industry rarely talks about such issues. So, before I discuss the current global import and export chaos that is seemingly run by George Costanza’s Vandelay Industries, I will introduce the basic principles.

An introduction to distribution channel management

Distribution is building relationships with suppliers, partners and resellers in the supply chain. There are two categories: upstream (those with input materials or information) and downstream (those who get the product to end consumers).

The company is the middleman. For Netflix, the upstream were those who helped to produce and store the DVDs. The downstream was the US Post Office. The upstream, company and downstream together create a ‘value delivery network.’

The network affects the whole marketing mix. The quality of the raw materials and components influences the product's price and brand. So will whether the company sells in Harrods, Trader Joe’s or Walmart. A quality downstream supplier can move products more quickly and cost more money – but it can also improve customer satisfaction. A cheaper one can do the opposite of each.

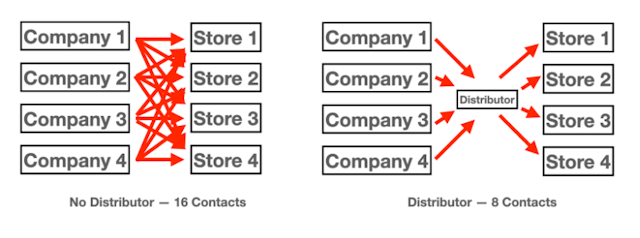

But why do companies even use distributors? Cutting out middlemen is a classic way to save money. Well, here is a quick explanation that I created.

Say there are four non-competing companies that each want to put their product in four stores. If each business would deal with every store, there would be 16 total contacts involving countless meetings and paperwork. With a distributor, the number of contacts would fall to eight at most.

Further, the distributor already has relationships with the stores. Cadbury might not know how many chocolate bars are sold every month at the Tesco at 294 Old Brompton Road in southwest London. But the distributor does. Marketers talk all the time about being ‘customer facing’ – but distributors are often in front of consumers the most.

How marketers and distributors can work together

Companies make large amounts of small numbers of products. Consumers buy small amounts of a large number of products. Distributors take large quantities of large numbers of products and then divide them among stores based on the demand at each one. Basically, they match supply and demand.

In this process, marketers give up some control in exchange for greater efficiency and physical availability at the bottom of the funnel.

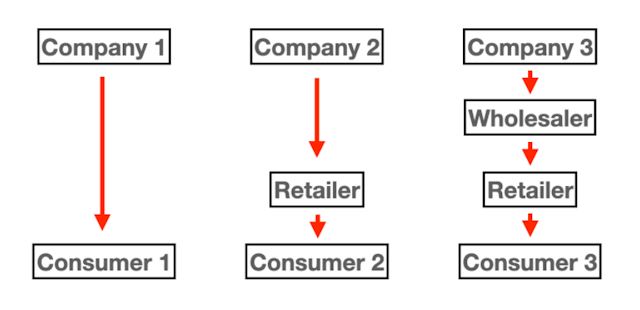

Now, each step between the company and consumer – such as a wholesaler and a retailer – is a level within the channel. Here are the three main B2C channels.

Each has pros and cons. DTC, on the left, often has higher profit margins and better relationships with customers. It also allows companies to sell at premium prices without having their products appear on shelves next to the competition.

If I enter an Apple store, I do not see Microsoft products. Women who sell Avon products at dinner parties are not offering Mary Kay there as well. Their physical availability is eliminated.

However, companies that do everything from production to promotion to distribution to sales need significant initial investment and have high overhead costs. Businesses that sell through retailers merely need to get their products on store shelves. The retailers themselves will take it from there.

Each model also has flows of physical products, payments and promotion. For example, Google might produce a new Android smartphone and run nationwide brand advertising campaigns. Retailers might then display them attractively on shelves, price them, have people trained to sell and answer questions and run direct response campaigns.

How to make and measure distribution decisions

First, every channel level should add some type of value for the consumer. In addition to product, price and promotion, this is a way for ‘place’ to be customer-focused as well.

Market research should determine what consumers want. Do they prefer easy, quick availability from nearby stores? Are they willing to travel to further away places for something extra? Do they want to buy in person, over the phone or online?

The ideal is to provide the highest level of customer service at the lowest cost. But that is impossible. It is like the old adage: “You can have it done quickly, cheaply and well. Pick two.”

At the cheap extreme, companies can have slow delivery, small inventories, large shipping lots and strict return policies. At the expensive extreme, businesses can have quick delivery, large inventories, small shipping batches and liberal return policies.

The key is to learn the amount of importance of these items to the target market and then aim for a targeted level of customer service at the least possible cost. A group of customers, for example, might not mind if delivery takes a while but still demand the ability to return items for any reason.

Second, companies must think about the types, numbers and responsibilities of intermediaries. Mass consumer brands usually have ‘intensive distribution’ in almost every store possible. Luxury brands do ‘exclusive distribution’ in one or a few chic places. Brands in the middle have ‘selective distribution’ in the, well, middle.

Third, businesses and distributors need to agree on things such as price policies and territory rights. Fourth, companies need to determine how to physically transport raw materials and finished goods. The standard options are trucks, container ships, trains and airplanes. Each has positives and negatives in terms of time and cost.

As far as distributors themselves, marketers should evaluate each potential one based on factors including years in business, locations, cooperativeness and industry reputation.

In terms of measurement metrics, the costs, the amount of likely sales and the profitability are obvious ones. There are also inventory levels, customer delivery time, treatment of damaged or lost items, and the effectiveness of promotional activity and customer service.

In the end, brands should remember that distributors are first-line customers and partners before the actual end consumers. Distributor satisfaction can improve customer satisfaction.

How JIT was one factor in the supply chain crisis

Now, why did I spend half of this column summarizing the basics of distribution? Simple. Just as a bad brief will lead to an ineffective advertising campaign, so will a mistake in one part of distribution mess up everything.

Which brings us to the worst business idea after the modern popularization of ‘mom jeans’: the Just in Time (JIT) inventory management system. JIT is one of those things, like an overreliance on ‘performance marketing,’ that look good on paper but can perform terribly in the real world.

Traditionally, the logistics function of inventory management is striking a middle ground between having too much and too little stock. JIT takes the latter to the extreme by having upstream raw materials and downstream finished products arrive exactly when needed rather than put them in storage.

Take your family’s meals. In JIT, you would plan every day’s individual meals, go to the store early in the morning, and buy only what you need for those three specific meals. Rinse and repeat every single day.

For a family of four’s breakfasts, you might get a small carton of eggs with a medium pack of bacon and one jug each of milk and juice. For the lunches, a loaf of sliced bread with a pack of lunch meat and two pieces of fruit each for everyone. For the dinners, a cut chicken along with four large potatoes, a large bag of vegetables and a cake for dessert. No more and no less.

Every single day, you would buy only what you needed. There would be nothing left over. It would be perfect efficiency – no wasted food or money.

The problem is that this scenario is a fantasy that would rarely happen in the real world. Few working parents can go to the supermarket every morning. But for some reason, large corporations decided a few decades ago that such a system would work for international supply chains.

JIT has its origins in a Toyota operating methodology in Japan in 1930 that was called ‘The Toyota Way.’ In the late 1980s, John Krafcik created the term ‘lean manufacturing’ while he was a production researcher and consultant at MIT’s International Motor Vehicle Program.

Eventually, ‘lean’ became ‘just in time.’ Accountants – who, like economists, know the cost of everything but the value of nothing – love JIT because, to them, having excess inventory is an inefficient waste of money on their spreadsheets.

But you know what is even worse? Unhappy customers.

My 2014 Macbook Pro has seen a lot. But in 2021, it is now an old man in computer years. The battery is completely dead. If the charger cable becomes a little loose for a split second, the computer shuts down and I have to reboot. Writing this column is a chore because The. Macbook. Is. So. Slow. It’s like waiting for Piers Morgan to have a rational thought on TV.

I ordered a new Macbook in September from the Apple store here in Tel Aviv. It is now early November, and the earliest it ‘may’ arrive is later this month. Why? The stores in Israel have been out of stock. And even though I know how supply chains work, part of me still subconsciously blames them.

With JIT, my skeptical thought has always been that any single point of failure could bring everything crashing down. But I could never have imagined the effects of a pandemic combined with Brexit, a lack of many raw materials and a labor shortage.

If companies get raw materials from upstream suppliers just in time, if wholesalers get shipments from companies just in time and if retailers get products from wholesalers just in time, all it takes is one thing to arrive not in time for the entire system to fall apart.

JIT is the perfect example of being ’penny wise and pound foolish.’ The idea has created a supply chain house of cards. Everything from Murphy’s Law to the Second Law of Thermodynamics says to prepare for the unexpected because chaos will always ensue. After all, there is even an old joke: “How do you make god laugh? Make a plan.”

Take the refrigerator example from earlier. Little Johnny’s football teammates might visit after practice and clean out the refrigerator. Little Susie’s girlfriend might unexpectedly pop over for dinner a few nights a week. Without any excess inventory – extra food – your family will go hungry.

According to Supply Chain Dive, 59% of companies in the US and 47% in the world would be unable to continue shipments for more than two weeks after a production stoppage because of JIT. That report was from March 2020. Note the month.

JIT is the distribution equivalent of spending your entire marcom budget on direct response for the quick benefit but then facing disaster because you neglected to build a long-term brand. Short-termism is running amok everywhere. It is gaining or saving $1 today at the cost of losing $10 tomorrow.

Luckily, distribution and communications can both play roles in alleviating the crisis.

So, what should companies do?

First, the marcom. Do not cut ad spend. The Wall Street Journal reported last week that some companies such as Hershey’s and Kimberly-Clark are cutting budgets. But cutting brand advertising spend is one of the worst things to do in either a recession or a supply chain crisis. Brand advertising is more about preserving and increasing future sales regardless of present situations.

Communicate proactively. Once a week, I send a WhatsApp message to Apple’s iStore in Tel Aviv to ask about my computer. I should not have to do that. Instead, be proactive about telling your distributors and customers about their shipments. I would love for the iStore to send me an SMS once per week automatically.

Tell customers when items are back in stock. Use email newsletters, SMS or even TV advertising and more to tell people when products are available again. Bonus: You know what items the members of your loyalty programs buy most often. They would love to know when you have them again.

Run holiday campaigns now. Yes, everyone hates how the holiday season seems to start earlier and earlier every year. But in 2021, we have no choice because customers should buy their Christmas and Hanukkah presents now to ensure that they arrive on time. Start the sales. After all, media plans are already being affected.

Second, the distribution. Drop JIT. The opposite of JIT is Just in Case, which focuses on having enough inventory for emergencies or sudden increases in orders. Increase inventory and lot sizes. Have multiple suppliers for the same raw materials and hire more staff than you need. And give your accountant that week off.

Create contingency plans. Crisis planning is not just for PR. Figure out a Plan B for every scenario ranging from a loss of an upstream raw material to your retail distributor closing shop because of a coronavirus outbreak. It might be too late for 2021, but doing a supply chain vulnerability audit is always a good idea.

Lastly, marketers – especially those who work only in promotion and communications – should familiarize themselves with their company’s distribution and supply chain. The 4 Ps need to be aligned together.

After all, ‘place’ can be a lot more influential than people think. Much commentary on the streaming TV industry has assumed that the company with the best original programming will succeed.

But success in streaming will seemingly depend not on one-off original products but on old distribution rights. People watch shows such as Friends, Seinfeld and The Office time and time again. (People turn to classic comedies for comfort in dark times.)

Netflix paid more than $500m for Seinfeld. So did NBC’s Peacock for The Office. HBO Max paid $425m for Friends. The big money in streaming lies not in product but in distribution – all in the name of building a loyal subscriber base.

Somewhere, Marc Randolph – one of Netflix’s cofounders – is smiling.

The Promotion Fix is an exclusive column for The Drum contributed by global keynote and virtual marketing speaker Samuel Scott, a former journalist, newspaper editor and director of marketing in the high-tech industry. Scott is based out of Tel Aviv, Israel.