Beware the bots: the threat of CTV ad fraud looms as viewership rates rise

Using spoofing tactics, bad actors can gain access to CTV servers, disguise bots as real viewers and even purport to run ads when no ads are present. As television viewership rates continue to climb, the threat of ad fraud grows. As part of The Drum’s deep dive into the future of TV, we unpack what marketers need to know.

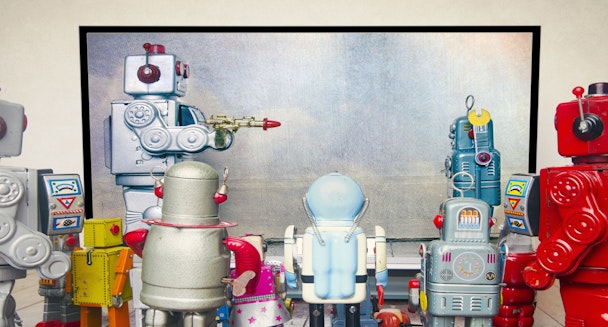

Bots can gain access to CTV apps and pretend to deliver real ad impressions

With consumers stuck at home, connected TV (CTV) viewership – and media consumption at large – has skyrocketed. While CTV ad inventory presents new, high-value opportunities for marketers, it offers comparably attractive opportunities for fraudsters and bad actors. Because the cost per impression (CPM) is relatively high on CTV compared to other formats like display advertising, the incentives for fraud are obvious.

Last year, a network of bots gained access to applications on more than a million Android devices and paraded as real users watching ads on smart TVs. The bot traffic accounted for an average of 650 million bid requests a day and tricked more than 6,000 CTV apps.

While Human (formerly White Ops), a leading ad fraud solutions firm, was able to successfully quash the operation, dubbed Pareto, the problem of cybersecurity continues to grow as viewership rates rise.

How does CTV ad fraud work?

On smart TVs, ads are served on apps like YouTube, Hulu and other ad-supported mediums via server-side ad insertion technology, which essentially allows advertisers to marry an ad on one server with the content on the screen (delivered through a different server) in real-time. The adtech infrastructure allows for some degree of personalization here too, enabling advertisers to serve ads to specific viewers depending on demographic factors, for example.

However, there are potentially many openings within this pipeline for bad actors to gain access to servers and supply fake data that defrauds marketers. In the case of what’s called ‘spoofing’, among the most common types of ad fraud activities, marketers purchase CTV ads with the promise that their ads will be served to a certain group of people, but the ad impression goes to a different device or a different group of people. Bad actors and their bots might indicate to marketers that they’ve paid for more premium advertising than they actually got – or even that there is an ad present when there actually isn’t.

It’s clear that ad fraud on smart TVs comes in a variety of forms, but it’s also becoming easier to commit, as CTV media buying increasingly shifts from manual to programmatic models. “Programmatic can be opaque,” says Tony Marlow, chief marketing officer at Integral Ad Science. “Marketers may not know exactly where their ads are running, and this opens the door for higher fraud rates.”

Another problem is that the CTV ecosystem is highly fragmented. With a wide variety of streaming platforms and publishers, buying and selling can look different based on a number of factors. There is no centralized or universal media buying hub. “[This] means that marketers have multiple ways to buy inventory and it gets complex quickly,” Marlow says. “Often marketers are faced with too many options – including direct-to-publisher, multi-channel platforms and aggregator platforms – and not enough transparency into where their ads will actually run. [They don’t have information regarding] the show, ad position, time of day and other critical factors.”

In the case of the Pareto attack, bots leveraged ad insertion servers on the server side. “They would basically say, ‘Hey, I’ve got traffic. I’ve got a user. They’re watching this thing, so come by.’ So the bid opportunity goes out to the marketplace through a bunch of middlemen and ultimately reaches a buyer or an agency acting on behalf of a buyer. If they purchase that traffic they then give instructions to insert their creative into the video stream that the user is watching,” says Michael McNally, chief scientist at Human. However, the Pareto botnet simply created the illusion that the process was running smoothly. In reality, the buyer was paying for a fake audience. By aggregating large volumes of fake traffic, fraudsters benefited from the commissions.

Ad fraud events like the Pareto operation hurt marketers and decrease trust in the system. David Dworin, vice-president of global advisory services and trust and standards at FreeWheel, Comcast’s technology platform focused on optimized connection between buyers and sellers, says that, even indirectly, ad fraud can hurt all those involved, including CTV publishers who lose out on monetization opportunities. But it’s advertisers who suffer the brunt of the impact. “Advertisers end up wasting money on advertising that is never seen by viewers, and therefore doesn’t work. Fraudulent publishers charge less than those with legitimate inventory, so advertisers looking to get the lowest CPM – rather than the highest impact – will get hit even harder,” he says.

Hurdles to stopping ad fraud

Recent IAS research indicates that more than one in four industry experts believe that CTV is more vulnerable to ad fraud than other formats. However, some disagree. Geoff Wolinetz, FreeWheel’s head of revenue, argues that CTV – and traditional linear TV, too – actually tend to be far less vulnerable to ad fraud than other IP channels. “These are server-side platforms, as opposed to client-side platforms. All the data is stored at the server level, meaning that by its very nature, there is more data protection surrounding it. Server-side versus client-side delivery platforms typically have less fraud.”

McNally sides with Wolinetz. He says that the vast majority of CTV is fraud-free and serves as a valuable inventory source for marketers. The problem, he says, is that the ecosystem is “signal impoverished”.

What he means is that there are some limitations to the amount of data that can be collected internally to verify that the impression occurred and was a real impression. “The telemetry that you get on CTV is simply less than you get from a lot of other forms of advertisements – and by telemetry, I mean what can be observed in the moment of the impression to verify that it was genuinely served to a real device, that a human watched it, that humans are interacting with the device in a normal way and that it is not simulated or scripted by bots.”

“The problem is exacerbated by the complexity of the CTV media buying and selling landscape,” says McNally. “Every path is different – there are all these different layers of advertiser to agency, demand-side platform to ad network, sell-side platform to aggregator, down to the devices themselves.” As a result, it can be challenging to determine just how much of a publisher’s purported traffic is fraudulent.

So, what’s the solution?

While it’s clear that the CTV transaction infrastructure, ad verification frameworks and security measures all need to be improved, there are some things that can be done today to mitigate the risks of ad fraud and other cybersecurity threats.

Crucially, McNally argues that technical upgrades are needed on the device level. “My Android phone has a hardware chip that attests that it is a physical phone and it was actually built by a given manufacturer,” he says, holding up his device. “The phone can prove itself in a privacy-safe and cryptographically safe manner. CTV devices don’t have that – they can’t prove that they are actually running code on a physical device.”

He says that if smart TV devices were embedded with similar hardware, the problem of ad spoofing on CTV could be rendered almost nonexistent because fraudsters would not be able to lie about the kinds of devices on which ads are being served.

More sophisticated ad verification technologies will also help mitigate the risk of ad fraud. Marlow says the industry needs “technology that helps to verify that marketers’ dollars are well spent and that publishers are compensated for quality content."

However, marketers don’t need to await widespread technical improvements in order to reduce the likelihood of falling victim to CTV ad fraud. One of the simplest actions that marketers can take is what McNally calls “responsible buying behavior” or “hygiene”. In essence, buyers should be more scrupulous about the validity of their reports and about the reliability of sellers.

This requires establishing stronger integrations between CTV providers and ad verification companies. Many verification companies, including Human, offer anti-fraud SDKs that can be included in CTV apps to improve visibility into what is happening within those apps. “If they’re correctly integrated, we can better determine what’s going on. And if something is being reported consistently as a high level of invalid traffic, that’s probably from a bad source. The buyer should probably make a choice to stop buying from those sources.”

FreeWheel’s Dworin agrees, stressing that the best thing marketers can do is buy CTV inventory from trusted partners with as few layers of intermediation as possible.

McNally also recommends that all parties involve comply with the Interactive Advertising Bureau’s (IAB) set of standards on supply chain transparency. These standards help ensure the validity of a seller’s identity by requiring sellers to submit what’s called a sellers.json file, which confirms their identity and lends to their trustworthiness. This information can then be shared across each stage of the supply chain.

Further, the IAB’s OpenRTB SupplyChain Object tool creates a sort of receipt that documents every player who was involved in the sale of a specific impression. Adherence to IAB standards creates greater transparency and enables buyers to more easily determine who is receiving payments for given ad impressions. Without comprehensive ledgers, marketers are left “playing whack-a-mole,” says McNally.

As CTV viewership continues to grow, marketers will need to remain vigilant in combating ad fraud to the best of their abilities and work with players across the ecosystem to improve the infrastructure.

“A variety of players across the CTV ecosystem have a role to play in securing the future of TV,” says Dworin. “Technology companies, especially device manufacturers and server-side ad insertion vendors, should consider implementing security mechanisms that make it harder for bad actors to spoof their devices. Industry trade groups have an important role in recommending standards. Platforms have an important role to play in acting quickly to remove bad actors.”

From late April until early May, The Drum is taking a deep dive into what’s in store for the small screen as we launch our Future of TV hub. And you can sign up for The Drum’s daily US email here.