The pandemic infodemic: how social media helps (and hurts) during the coronavirus outbreak

Right now, the world is battling a coronavirus epidemic. It started in December 2019, when a group of people from China’s northern Hubei province developed an unexplained pneumonia-like condition. By the end of the month, the local scientific community managed to pinpoint the source of the disease and establish its link to the SARS virus that terrorized the world 17 years ago.

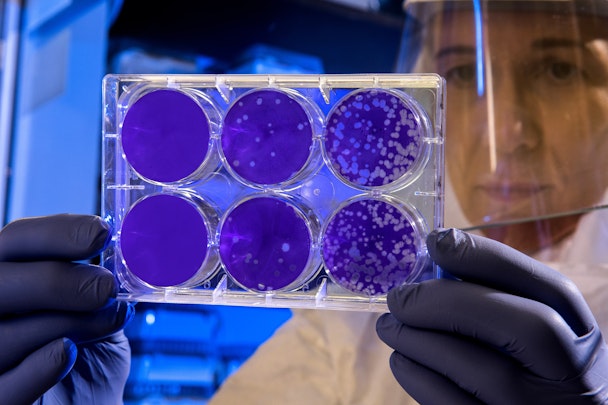

The world is on standby for a pandemic / Photo by CDC on Unsplash.

As 2020 rolled around, the outbreak turned into an international pandemic. Each new country the virus spread to fuelled panic and demand for information regarding the disease. As a result, social media became both an indispensable source of vital information and a fertile ground for dangerous rumour-mongering, with claims of equal shock value but varying truth making big waves across the world. The WHO Director-General even stated: “We’re not just fighting an epidemic; we’re fighting an infodemic.” This situation is the testament to the raw power of social media, and a sign of how much we achieved when it comes to curtailing the spread of dangerous lies online. Let’s talk about it.

Pandemics of the social media age

The coronavirus outbreak wasn’t the first to arrive in the age of social media: at least three other international pandemics occurred in the ten years preceding it. The H1N1 (swine flu) pandemic, the Ebola epidemic and the Zika outbreak all had prominent, and widely documented, influence on social media conversations. Just ten years ago, NGOs weren’t necessarily well-equipped to communicate risk information online. The people used social media to look for directives, but unreliable and/or unofficial sources had the loudest voices.

By the time 2014 arrived, health organizations were much better prepared to launch their campaigns, and influencers helped them get exposure. But the social networks themselves had trouble identifying malicious actors and dealing with misinformation. These days we’ve made tremendous progress. Social networks have matured in terms of their functionality, big organizations got better at communicating online, and, following the large-scale misinformation campaigns of 2016, people have gotten a bit better at telling truth from fiction. So, what role does social media play in this unfolding story?

Source of verifiable information

China, famously unprepared to take the stage during the 2009 H1N1 outbreak, learned its lesson, being upfront and transparent about the coronavirus situation on social media. In the days following the initial news, there was no shortage of verifiable information from official Chinese sources.

WHO and other public health organizations also use social media to inform the public about the outbreak, and control the panic. Of course, it doesn’t mean that misinformation is not being circulated among social media users. For many people, conspiracy theories are a natural response to the senseless cruelty of this crisis. They offer clarity and an opportunity to blame someone for the havoc. So it’s not unreasonable that a number of dangerous conspiracy theories 'blew up', offering interesting, albeit completely incorrect ways of viewing the situation. Some claim that the virus is a biological weapon, created by either the US (to kill Chinese people) or China (to kill Americans). Some claim that the outbreak was orchestrated by big tech - to undermine China’s status as the world capital of high-tech manufacturing.

Social media websites are actively fighting this misinformation and fearmongering. Chinese tech giants, already well-versed in censorship, put their tools to good use to prevent the spread of such lies. The creators of WeChat — China’s number one social media platform — are using a popular fact-checking platform to dispel harmful misconceptions. Western websites, such as Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, are also actively working to ensure that only correct sources get amplified. When people search for ‘coronavirus’ on these platforms, they’re less likely to encounter any unsubstantiated claims than they would during the recent Zika crisis. Content from ‘reputable’ accounts is given priority, while amateur claims are being scrutinised and factchecked.

Of course, no fake news — filtering algorithm is perfect. As coronavirus became a trending topic, many people tried to profit off its popularity in ways that couldn’t have been predicted. Several teen bloggers pretended to be infected to elicit shock from their peers, pity from their online followers, and, most importantly, clicks. Stunts like these cannot be controlled as well as the claims of international conspiracies, but they’re still largely illegal — and the perpetrators are likely to face consequences for their acts of sowing panic on purpose.

Method of communication

Multiple cities in the Hubei province are on lockdown to prevent the spread of the virus: more than 50 million individuals are prevented from leaving their cities. Around the world, those suspected of harbouring the disease are quarantined inside their homes or in medical institutions. In these conditions, social media serves as the only reliable way for the victims of this virus to communicate with the outside world. The demand for first-hand information about the outbreak fuelled the popularity of coronavirus vlogs.

People are eager to tell their stories and document their daily lives in the face of this deadly disease. This particularly applies to people in highly isolated environments, such as that of the Diamond Princess cruise liner — a coronavirus-infected ship. It was on lockdown for most of February, with more than 3500 people onboard, including 700 coronavirus patients.

The passengers weren’t allowed to mingle, and only a few were evacuated. In the face of this horror, social media was the only way for the passengers to stay in touch with their families and the world at large. They made vlogs, blogs, and appeared on live TV from the eerie comfort of their cabins. Chinese citizens, particularly those who live in the North, avoid going outside and use social media to curtail the risk of being infected. They can keep in touch with their friends, get the latest news, and order food thanks to social media.

Support infrastructure

Social media has also been instrumental in helping improve the situation.

Like other similar disasters, it gave birth to a fair share of online fundraisers, both within China and outside its borders. People are giving money to struggling hospitals, as well as individuals at risk of dying from the disease. Big companies like Western Union and Tencent are also joining in, encouraging their clients and users to donate to the cause.

Scientists are using social media tools to collaborate. The coronavirus genome was openly published early on during the outbreak, allowing thousands of researchers to brainstorm possible solutions, cures and explanations.

Regular people can simply use social media to provide moral support to those affected by the deadly virus. In a typically Chinese display of solidarity, WeChat users from across China published pictures of their local food in support of those in Wuhan.

Finally, social media provides a sort of collective grieving space. Events like these can be hard to process psychologically, and even harder to make sense of. When one of the scientists to first discover the virus succumbed to the disease, his death sparked conversations about the selfless bravery of people fighting the outbreak. His memory was honoured by thousands of netizens.

Takeaways

Whereas the coverage of earlier pandemics’ social media influence was largely focused misinformation, it wouldn’t really be fair to do the same here.

Social networks are doing their part by creating new tools to tackle fake news and conspiracy theories. At this point, they’re doing more good than bad to help people affected by the virus. They fuel scientific collaboration, create fundraising opportunities, and — perhaps, most importantly — helps the quarantined people overcome their isolation.

Social media can be an unstoppable force, especially in times of crisis. MNFST, our crowd promotion platform, can help your brand leverage it, and generate genuine excitement for your product.

Michael Sokolov is the co-founder of MNFST

Content by The Drum Network member:

MNFST

MNFST is a digital profile company. We are on a mission to inspire creativity and democratize influencer market in the same way Airbnb and Uber democratized property...

Find out more