An Hour of Advertising with… Jonathan Burley

When Maxine, one of Hour of Advertising’s fantastic designers, received the transcript from my interview with Jonathan Burley, her first response was: “You can see why creatives love working for him.”

Jonathan Burley

And indeed they do. Burley is one of the industry’s most decorated creative directors. He has transformed the fortunes of some of the UK’s most powerful brands. And he’s mentored a fair chunk of the brightest creative minds running advertising agencies today.

Burley began his career at two of the industry’s most iconic agencies – WCRS and HHCL, working with people like Steve Henry, Leon Jaume and Trevor Robinson. After working his way up from ‘oik’ to creative director, he moved to Leo Burnett, taking on and transforming McDonald’s advertising from hated to heartfelt.

Following a five-year spell at Leos – during which he was appointed group executive creative director and oversaw one of the world’s most awarded campaigns in ‘House of Cards’ for Shelter – Burley moved to Rathbone Street and CHI & Partners. As chief creative officer, he led the agency to become the UK’s most awarded independent creative shop.

Most recently, Burley was at Y&R as chief creative officer. His spell was short lived, leaving in rather dramatic (for this industry, anyway) circumstances when the entire management team was dismissed following Y&R’s merger with VML.

Due to the nature of his departure, Burley can’t talk much in our interview about leaving Y&R or what he’s doing next. And while the journalist in me wants to sniff out a story, that’s not what this series is about anyway. We want to get under the skin of the subject, to understand their outlook on creativity and talent and to get them reminiscing on why they fell in love with our industry in the first place.

In our chat, Burley does all that and more. He’s effortlessly engaging, charming and articulate, even when approximately 50% of every sentence is a profanity. So perhaps it’s apt that we open with our usual first question – does he remember the first time he fucked up?

Part one: dreadful starts, terrifying ECDs and working in old school creative departments…

Do you remember the first time you really fucked up?

My first ever ad was one of Campaign’s Turkeys of the Year. That wasn’t a great start. We were on placement at WCRS and were asked to ask write a research script for Caffrey’s Irish Ale. We were writing a script as fodder, and our ECDs Larry Barker and Rooney Carruthers were writing the ‘real’ one.

For some unaccountable reason, our ad came out top in research. And the ad – oh, good God – was based on this really clunky, possibly mildly racist construct of an Irishman abroad (in our case, for reasons lost to time and shame, an Irish biffa on holiday in Cuba) who has a sip of a Caffrey’s and is immediately transported back to the auld country.

It was a horrible script. We flew to Cuba for three weeks, shot with Jonathan Glazer – who was also very early on in his career – and then had another three weeks in Ireland shooting. It cost millions of pounds. They shut down a quarter of Havana for us and we created a real carnival, setting off these massive illegal fireworks and had what felt like the entire city dancing in the streets. It was an amazing experience for a fat kid from a Pompey housing estate. But it ended up, honestly, being the worst ad you’ve ever seen. So cheesy, so shameful, so embarrassing to think back on. And it ended up something like number 8 or 9 in Campaign’s Turkeys of the Year.

So not the worst then…

I think it must have been a particularly bad year in advertising. And it was nearly the end of my nascent career. I remember Rooney in particular taking it very badly that we’d won the script and then produced this Christ-awful turkey…

Being transported immediately into this lifestyle of amazing shoots in amazing locations – you must have thought you’d made it already!

I remember we were sitting in the street in Havana at three in the morning, with our own festival going on, and being told by Larry: “You do know it’ll never be like this again, don’t you?” He wasn’t wrong – I’ve hardly been on a foreign shoot since.

It wasn’t something that interested you?

Not hugely. I’ve never been one of those creatives who can’t wait to get on a plane for a foreign jolly. I think I went on one more actually. But certainly not as an ECD – because I think if you go on those you’re just stepping on the toes of your creative director. It’s a ghastly ECD wanker thing to do. So he was absolutely right – almost every ad I made afterwards was shot in some shitty studio outside the M25. Come to think about it, the only other ad I shot abroad was also in a shitty studio.

So your first project saw you as a junior team put up against a stellar team in Larry and Rooney – was it really as competitive as it sounds?

It was in those days. But it was at its best when it was a good-natured competitiveness. One of the things I’ve learnt over the years – particularly at HHCL – is that the competition is yourself, not other creative teams. Otherwise you get this ugly, non-collaborate creative department. I’ve heard some terrible stories from agencies I won’t name, where you hear ghastly things going on – creative teams stealing work from other people, hiding briefs in the broom cupboards, that sort of unpleasant bullshittery.

But for us it was usually entertainingly competitive. Lots of piss-taking and banter. We always found it a laugh to go up against senior teams, a chance for us to learn how to do things properly from people better than us whilst being the cheeky little fuckers that we were. So going up against Larry and Rooney was fun – even if there was genuinely no way we should have won that.

Starting at WCRS, what was that creative department like?

There was an interesting stretch of class within the department. You had Leon Jaume, who was (and is) the most exquisitely louche man I’ve ever met. A brilliant, generous CD team called Robin and Robin who took us under their wing – Robin Weeks was the most spectacular human being. He was like Lawrence of Arabia blended with Jon Pertwee-era Dr Who, with a touch of Jeffrey Bernard thrown in for vinegarish good measure. He’d wander the department in a white, red wine-spotted linen suit, hurling beautifully-modulated insults at whoever crossed his path. Then you had oiks like me and my partner Ian, Darren Bailes, Al McCuish, etc. We were all real scrubby little kids from council estates.

So in that respect, I guess it was kind of diverse. But fuck me, it was unappealingly blokey. There was no diversity, no female creatives at all. The department just wasn’t built that way. And there was so much money and so many clients sloshing around and it was still seen as such a glamorous industry that people would act like they were rock stars. The number of creatives who fancied themselves as Liam Gallagher… that cocky, misplaced confidence.

And that’s something that’s changed? That confidence?

It seems to me that the only people who can afford to take the risk of trying to get into advertising these days are the children of the very middle-class, where it doesn’t hugely matter if their early career fucks up. When I was a kid it really mattered if it fucked up. So our passion for it was pretty intense. You felt disproportionately fired up about advertising and its importance in the world. Now, there’s a certain sense that it doesn’t matter so much. I’m not sure you get quite the same levels of burning passion that you used to have. And there’s definitely a far more well-spoken creative department than when I was a child.

The envy you felt when you heard that some people in the creative department were on £25,000… There was this lovely creative guy called Mark Cooper who took all the creative kids under his wing. And I remember we all went to the pub once, and he went to the cashpoint and got out £30 to buy beers, and we were all going: “Fuck me, what must it be like to be able to get 30 quid out of the cashpoint and not worry about it?”

So it’s fair to say you weren’t on that when you started?

I think we got paid about £20 placement money, may have sometimes had our train tickets paid for. We slept on mates’ sofas and shit. Christ, I’m making it sound like that old Monty Python sketch: “You think you had it bad…” It wasn’t like that. We were in our early 20s and it was exciting to be part of this shiny industry, and we’d spent most of our college years living in far scuzzier environments. At least we got free coffee and beer and could steal toilet rolls to take home with us…

Was there this huge admiration and respect for the ECDs, holding them up on a pedestal?

No, not at all. Were we scared of them? Oh, yes. Especially one of them, I was terrified of him because of his notorious bad temper and his propensity to take things badly when you least expected it. But respect? I think young creatives quite rightly want to kill their parents. You always think everyone above you is a little bit shit. It wasn’t until I became a CD myself that I recognised the impact that CDs had had on my work as a creative. You’d always think their feedback was there to make your work worse. Of course you’d have to shut up and get on with it, but behind their backs you’d say they were rubbish old men (always men, in those days) who didn’t know what the fuck they were talking about.

So I’d say there was a healthy disrespect. As there should be. You want the next generation of creatives to think that you’re behind the times, daddy-oh - that you’re a bit decrepit and can’t see the value of the brand new idea. The last thing you really want is for them to think you’re a God. Unless you’re Steve Henry, of course - because he was a God.

Part two: an anarchic time at HHCL, finding the right creative partner and what to look for in a creative team…

Were you ever an advertising scholar?

Never. Maybe I would have been if I had a slightly different career path. If I’d gone from WCRS to TBWA or AMV. Both brilliant agencies, but very much immersed in the lore of advertising. But I went to HHCL. And HHCL’s mindset was very much ‘everything that’s come before this is shit’. Every ad that Steve Henry would write was a fucking suicide note to the industry. And if you look back at some of these things now, they would be feted and lauded because they were trying to do things fundamentally differently. It wasn’t just making a telly ad or writing a clever poster campaign. People would spend days – genuinely days – writing the legals for a Tango DRTV campaign. Just to make themselves laugh. The legals would always be very funny on an HHCL ad.

I spoke to Trevor Robinson about being at HHCL and he said similar things – was the cult of HHCL truly that great?

It was an agency that genuinely believed in being provocative for the sake of it, that the worst crime you could commit with your advertising was to go unnoticed. I remember a creative team wrote an opera about the Topic chocolate bar. Topic the opera, a two-hour long radio campaign. Fucking hell. It was insane. But it was that level of ambition that at the time was unsurpassed. You’d never find that in a D&AD Annual. Maybe you would now, but certainly not then. It was a crazy place. We weren’t ad scholars, we were the opposite of ad scholars. We were all ad idiots.

Could it quite quickly chew up and spit out the creative teams that didn’t fit the bill?

Well, they just didn’t hire people who didn't ‘fit’ in the first place. There was a truly ferocious interview process. My partner and I had eight rounds of interviews. And that wasn’t just with Steve Henry and Axel Chaldecott, that was meeting with the head of planning, with other creatives, with HR, with the head of TV… you went through really difficult interviews because they wanted to get every hire just right. They’d try and provoke you in the interviews – try and get a rise out of you so they could see how you’d work in a very particular way. We had very nearly run out of patience with the whole thing when the headhunter called us to say we had got the gig.

So you never had what you’d think of as ‘traditional’ creatives there. You had Trevor (Robinson) and Al (Young), Dave (Buonaguidi) and Naresh (Ramchandani), Jim (Bolton) and Chaz (Bayfield). Very different sorts of creatives who all had very weird backgrounds. And very different ways at looking at the world. So those teams you describe – who perhaps would create very lovely AMV-style TV ads or a beautiful bit of DDB print – they just didn’t get hired.

How do you find the right creative partner? When do you know it’s right?

I’ve had two ‘creative marriages’ my career. My first one was to my old partner Ian Williamson. And we used to fight like cat and dog for some reason. We were weirdly competitive with each other. I don’t know why – I suppose it’s just like any relationship isn’t it? A chemistry which sometimes works, sometimes doesn’t. We were very different people and with very different working methods, but we did share a particular dark sense of humour and an ambition to be ad-famous. That ambitious tension between us, coupled with a shared ability to laugh at our own farts, I think helped us succeed at HHCL. But then I was promoted to CD and Ian moved to BBH.

My second marriage was to Jim (Bolton). Which was very different. We both have fundamentally different minds, but have never shared a cross word. Well apart from once in the overly-tooled toilet of a crappy member’s club, but that’s not a story you need to hear. Jim is the ‘creative’ one and I’m the ‘logical’ one. I like to think I’m good at reducing things and making them neat so that they work. Whereas Jim’s spectacularly good at going ‘I saw this crazy shit out of the window of the bus so what about if we did this even crazier thing in an advert…’. It was a very good left side/right side of the brain dynamic.

You and Jim went to Leo Burnett together but then you became ECD. Did that change your creative relationship as a pair?

Jim had absolutely no interest in being an ECD. But he was so important to have working with me. I’ve always believed in having a creative department that has fun. And by that, I don’t mean going down the pub. I’m not one of those “Hey, it’s a Friday, let’s all go down the pub and get fucked up” kind of CDs – it’s never been my personality, and it’s probably a rejection of that early-90s laddish ad culture I never felt comfortable with. But what I have always tried to build is a creative department that’s not just talented, but all gets on really well together and has a laugh.

Jim has always been an excellent catalyst for that. Jim is a lovely, gentle man – apart from when he’s drunk and he’s a ferocious human being. He’s always been a brilliant creative and both clients and teams absolutely love him, so for him to come in and be my support has been vital. He’s no interest in being an ECD but he loves being a great CD. And he has run amazing pieces of business.

So do you have a double-act routine?

He comes in and leads by example in a different way. I’d always come in as ECD and say: “Let me show you the type of creative people we could have around us to help us make this a great agency…” and then open the door to someone like Jim and create a department in that image. A department that’s imaginative, sweet and generous, who get on and whose only competition is themselves wanting to make the work better.

When hiring, what qualities do you look for in a creative team? What makes them work?

It’s a weird thing I’m about to say but, after the table stakes of a body of great work, I do look for personality first. I know it shouldn’t be a marker of a great creative team, and some agencies have been very successful not putting this as a factor, but I’ve always liked teams that walk the floor and are incredibly ‘present’. I don’t mean that they always need to be at their desks, I don’t mean they need to be there at 10 o’clock at night and weekends or any of that dreadful bullshit, but teams where I feel their presence strongly. Because teams like that can help inspire the department.

I was fortunate enough to have Rick Brim (the current chief creative officer of Adam & Eve/DDB) as one of my creatives at both Leo Burnett and CHI, and I always thought that his greatest weapon was his almost ridiculous positivity and energy. If you have someone like that in a department it can supercharge an entire agency. A group of creatives who are fun and open-minded and who everyone wants to hang out with, you’re onto a winner. If you’ve got the sullen creatives who sit there in their glass offices and hide their work and glumly stare into space, then that can infect the personality of the place. The creative department should be the engine of the agency.

So it’s personality first…

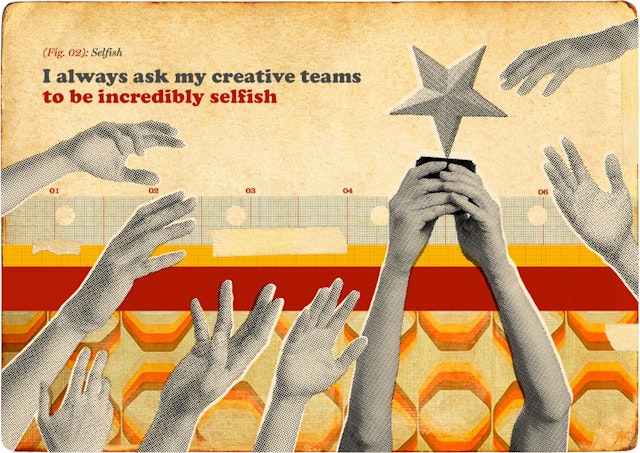

…then the second thing I look for is selfishness. I think that the job of being an ECD or a CD is to worry about the detail. The little things that make something right. The job of being a creative in the department is the opposite. Don’t worry about the detail, don’t worry about being right, worry about surprising me and exciting me. Then we can make sure it ticks the mandatories for the client, so if the client hates blue then we can make it pink, etc. I’ll worry about all that, you just worry about being provocative, exciting, different. Because if the creatives are spending all their time worrying about the detail, then I personally think that can be stifling for them.

So I’ve always said to creatives that if they come and work with me, I’d want them to be incredibly selfish. To concentrate solely on coming up with the work that will excite them and the agency rather than being terribly helpful and responsible. If I’ve got a department of ten teams, and all they’re doing is focusing on doing a piece of work that makes them famous or helps them ask for a pay rise, and I get one of those a year from every team… then, even with my crap maths, that makes ten amazing pieces of work that year. Which makes the department look good, the agency look great - and me look fucking incredible. Selfish, see?

So personality first, selfishness second…

And being good drunks third. I’ve had lovely people who are strangely angry drunks work for me before - and it’s just horrible. Especially at the Agency Christmas Party when they’re poking me in the chest and aggressively asking for a pay rise.

Part three: playing the ‘what if’ game, the tricky transition between creative and CD and building relationships with the rest of the management team…

You’ve had a lot of great people work for you. Can you tell when a young creative comes in that they’re going to run an agency one day?

It’s not always obvious. I suppose it depends whether they genuinely want to or not. The weird thing about being a creative is that it’s fundamentally different to being a suit or a planner – that’s not me being dismissive, by the way. It’s just that, as a creative, you’re not taught on the job about how to be a boss. As a business director you’ve got IPA courses, you’re trained how to manage a team. Being a creative, you’re awarded for doing good creative work by suddenly being given a managerial position. You win some awards and are made a CD, you get some good work out and make your clients happy and you’re made ECD. But doing great work and managing a great creative department are hugely different jobs.

There’s a game you play as a creative, where you’ve got four things on at once and you play ‘what if?’ You project a year on, you’ve had all the work made and you’re the most famous person in advertising. That’s what I want from a creative. But being a CD is slightly different. Your desire is to get the best piece of work you possibly can through a client, get them on board and excited, help them get their minds in a place that allows everyone to do better work in the future. It’s a very different job. So it’s very hard sometimes to recognise when a person comes in if they’re going to transition from being an amazing creative into an amazing CD.

Are there examples of those you’ve worked with who have and haven’t been able to make the move?

Well I’d say Rick (Brim) and Dan (Fisher) showed they’d be great CDs early on; they absolutely had that passion and enthusiasm and ambition you need to make the leap from making to leading. Watching them over the years – I worked with them for four years at Leo Burnett and another few at CHI before they went over to Adam & Eve – you could just see them honing their managerial skills. They had a rare, instinctive generosity with other teams. Ross (Neil) and Billy (Faithfull) were my first ever hires at HHCL and they’re now running departments.

But I’ve worked with some amazing creatives and creative teams who could just never let go of being a creative. They couldn’t move from being selfish to helping others. And they would say the worst thing you could ever hear as an ECD from your CD, which is ‘but I gave them that idea’. Of course you fucking did, that’s your job! Lord knows how many times when I was young that a great creative director like Al Young gave me the idea. I won’t remember them because in your head you convince yourself that you came up with them all yourself, but good creative directors help you get there.

How did you personally handle the move from creative director to executive creative director?

I think I was a much better ECD than CD. Because I think they’re fundamentally different jobs. Becoming ECD was a huge learning curve when I was offered it at Leo Burnett. You take on responsibilities around things like process and how you portion out time on clients. Stuff I learnt to love. You had to learn how to pitch, too. And I mean in terms of pitching as an ECD – you’re not just a creative reading out scripts, you’ve personally got to convince a client that they want to work with your agency.

And you enjoyed that?

I think I thrived off it. I’m the type of person who quite enjoys having too much on. And I absolutely don’t mean that in a ‘workaholic’ way. I’m definitely not that. I start quite early in the day, but I always leave bang on home time. I don’t believe in working late, I don’t believe in working weekends. I find that all bullshit. It’s old school adwank bullshit. I’ve always thought that if you can’t get your work done during office hours, you're not particularly good at your job.

But I do get bored easily; I’ve got a horribly short attention span, so I like my brain to be whirring during working hours. So, for me, the joy of being an ECD is to be able to go ‘I’ve got an hour to think about Argos, then I’ve got an hour to think about Samsung, then I can do some stuff on The Prince’s Trust, then I’ve got the Bird’s Eye pitch…’. But not everyone gets such a thrill form having their mind skitter all over the place.

What about your relationship with the rest of the management team? How important is it that you get on with the CEO, CSO etc when you’re ECD?

Oh it’s hugely important. It’s important because you’ve got to believe in each other. I’ve been lucky enough to have a couple of those relationships during my career. At CHI, for example, we had a really tight team. It was me, Sarah (Golding), Nick (Howarth) and Neil (Goodlad), and we were tight. We shared an office and we had a laugh - although undoubtedly the fact I used to continually dick about got on their nerves now and then. But when bad things happened, we were there to support one another, and when good things happened we celebrated together.

So it’s incredibly important to like one another, but that doesn’t mean you have to always get on. Goldie and I – Christ, how we used to bicker. Terrible rows that’d end with one of us storming out of the office going ‘fuck this’. Usually me, as it would be an excuse to go outside for a cigarette. And then five minutes we’d have hugged and made up. When it comes to defining a good team, it’s not about never arguing. It’s about how well you make up.

And you had the same at Leo Burnett?

Paul and I have a great relationship, but we’ve certainly had our arguments. We got on each other’s tits hugely now and then. I think our different personalities allowed us to neatly balance each other out, however; when one of us was fucked off and feeling sorry for themselves, the other was all happy-clappy positive without a care in the world… as friends, we instinctively knew how to get the best out of one another for the sake of the agency. You look at the agencies that thrive – famously the relationship between the Adam & Eve guys was incredibly tight and I’d suggest that chemistry was a fundamental part of their success. I’d say the same went for Johnny (Hornby), Charles (Inge) and Simon (Clemmow) when they first started CHI. I get the feeling there’s a similar relationship between the Uncommon lot, Lucky Generals..

Part four: a culture shock at Leo Burnett, working with marketing directors and the secret to McDonald’s success…

When you left HHCL to go to Leo Burnett, you were moving to a very different culture, a very different type of agency. What was day one like?

Day one was fucking ghastly. It became non-ghastly, but when we first joined, we’d come from HHCL that was very small – actually it was about 80 people and looking back that’s not that small, but it felt very small – and most of the stuff we made ran at 2am on obscure satellite TV channels so was only ever seen by students and stoners. Barring the agency’s work for Sky, there wasn’t a huge amount of creative output by the end. And suddenly we were going into Burnett’s, which had this enormous creative department, a lot of old, white men – ourselves included! – who were all incredibly lovely, but terribly old school in their work ethic and output. Everybody had an office they hid in all day, it was out in the middle of the arse-end of nowhere, we started in January when it always seemed to be dark and raining…it was all just very different.

But getting to know everybody and eventually becoming part of the leadership team, it ended up being the most like a family of anywhere I’ve ever worked. There were great people there in every discipline, there was a genuine sense of camaraderie, and it was a funny, funny place to work. But, Christ yes, at the beginning it was a vicious shock to the system!

And you took on McDonald’s, which doesn’t really do ads that run at 2am…

It was the steepest learning curve of my entire career. When Jim and I joined, the first brief we had started with the words ‘…as you know, people hate McDonald’s…’. It was just after Supersize Me and people loathed the brand. Even people who loved it at the time wouldn’t sit in the window when they went in to eat a Big Mac, so that no-one could see them from the street.

Nobody wanted to work on it. Genuinely, people would pretend that ‘morally’ they wouldn’t work on McDonald’s. That was of course bullshit – what they didn’t want to do was do another horrible advert. And I’m not going to lie to you, neither did we. But we were new, and we didn’t have a choice. And initially we did some painfully ordinary work.

What changed?

We met Jill (McDonald, the McDonald’s CMO) and Steve (Easterbrook, the McDonald’s CEO). And I remember at the start we had a disastrous meeting with Jill, where Jim and I were sharing some silly, nonsense scripts, making ourselves laugh and nobody else. It got back to Bruce (Hains, then Leo Burnett CEO) that we’d had a bad meeting, and he pointed out a very simple thing. He said: ‘Jill’s come from British Airways, and when she sees her old friends from BA for dinner on a Saturday night she wants them to say, “I saw your McDonald’s ad and it’s pretty good,” rather than “Your Big Mac ad is a bit embarrassing, isn't it?” She wants strong, populist, middle class advertising, because that’s what she wants the brand to become’. And it’s the best bit of advice he could have given us. Because that’s what we spent the next three years working hard to create.

There was a lot of thought from the entire team that went into the creative strategy, that went into building the brand in comms terms, developing a construct and a tone of voice that lasts to this day. I’m not taking credit for that - it was down to the client to urge the agency to do it. And I’m certainly not taking credit for all the great work that’s been created on the brand since. But that initial work from both agency and client is the main reason why it’s now an account that people want to work on. It’s now a truly great everyman brand. It’s got heart and soul and a client and an agency who love and still believe in the product. And I’m not sure it gets the credit it deserves for its longevity.

How do you get the balance between building a brand and keeping yourself interested by doing short-term, impact pieces too? Because I’m sure when the fifth McDonald’s Christmas campaign comes around, you must start to feel a bit tired…

I suppose it all depends on the brand. I know that sounds like a cop-out. But I had an interesting conversation recently about in-housing creative departments. My point of view is that to a degree I disagree with John Hegarty’s point that in-housing will end up sapping all the life out of people, or attracting low-rent creative teams. He’s right if that brand is something like Tate & Lyle sugar, or Hovis, or Andrex toilet paper; I wouldn’t want to work in an in-house bog-roll agency, this is true.

But if your brand is a platform – like Sky or BBC or Google, say – then I genuinely believe there are enough expressions of, and nuances within, that platform to make it a truly interesting creative job. And I think you can find ways of keeping longevity and creative interest, you just have to find ways to ensure that the brand idea is broad enough that it can keep being reinvented. And a great platform can be an idea, a purpose, as much as a brand. It’s an obvious one, but look at ‘Just Do It’ – it’s a platform that’s broad enough that you can have ‘Nothing beats a Londoner’ and the Colin Kaepernick work, two outstanding and very different campaigns, under one umbrella.

What was your relationships like with marketing directors? Were you one of those ECDs who looked forward to seeing their clients and working with them?

Very much so. I mean, obviously it depends upon the client, but that’s like any human being. I would regard myself fortunate for having worked with some fucking great clients. Along with McDonald’s, the BBC clients were geniuses, the Argos team I loved working with, they were really supportive and truly brave. Of course, there have been a few clients who were vicious and stupid and who I dreaded meeting, but on the whole, I’ve always enjoyed meeting bright clients.

The hard bit you always get – and I don’t know what the answer is – is that there’s a culture of fear that you get in marketing these days.

Why’s that?

It seems that marketers fear losing their jobs now in a way that I don’t think they used to worry about. And because of that fear, a lot of marketing people have a tendency to spend their time second-guessing. And it’s that second-guessing that makes a client – or an agency – really difficult to work with. If you’re doing that, you cannot allow your ambitions to run free in order to make the extraordinary things that actually make a difference to a business.

So it’s down to the culture of the business, rather than the sexiness of the brand?

To be honest it’s all down to the individuals you’re working with, not the brand itself. I’ll give you an unnamed example – I’ve worked with two quite similar charities over the past few years. One had the most caring, intelligent, grateful and ambitious marketing team, and we worked together to do some quite provocative and exciting work. Won awards, made a difference, all that good shit. The other was a far bigger charity, but had some of the most vile, self-serving, lazy, finger-pointing, shit-down biffas working there. Truly unpleasant buffoons. And the work was absolutely shocking. Total waste of money for a truly great cause. So, one hundred per cent it’s all down to the individual.

That’s not to say the culture of the company can’t also make a difference, mind. McDonald’s, for instance, they do things that people don’t talk about. The way they have job shares for working mums and dads. The way they support, encourage and develop people, whatever their background. The atmosphere never felt aggressive, it was never finger-pointing. But then you go to other companies, and the ghastliness of the business shines through. I’ve worked with brands where you’d go in and it was just sexist, racist, with people at the top always looking for someone to blame. I guess people hire in their own image, so finding a business with the right ethos and right people is much more attractive to me than finding a supposedly ‘sexy’ brand to work on. it’s a cliché, but it’s true - we work in the people business, so being surrounded by the right people is always the quickest way to succeed.

Artwork by Maxine Gregson

For more from the Hour of Advertising series, click here