Personalisation will be 2020’s most overhyped marketing practice

Personalisation was the US Association of National Advertisers’ 2019 marketing word of the year, but the idea’s popularity has been largely the result of martech companies successfully promoting their own personalisation technologies.

/ Photo by Markus Spiske temporausch.com from Pexels

Here are just a few examples from last year alone.

Accenture created an Interactive personalised Marketing Index (PDF) claiming that “almost 70% of consumers want companies to personalise their communications”. And what does Accenture sell? Marcom personalisation. Seismic commissioned a report stating that personalised customer experiences are the biggest opportunities for effective sales enablement. What does Seismic offer? Website personalisation.

WebEngage claimed in a webinar that “hyper-personalisation is the future of marketing”. Not surprisingly, the company sells messaging personalisation. Evergage’s 2019 personalisation study found that the practice “is clearly a top priority”. Of course, it is a personalisation platform. Pros creates personalised selling solutions and – no big shock here – commissioned a report stating that B2B buyers want personalisation.

Manhattan Associations sponsored a study stating that young retail shoppers are driven more by personalisation. The company’s technology creates personalised shopping experiences. Kevin Sieck of LatentView Analytics wrote in The Drum that “the need to mimic the human, in-person process and give customers a personalised experience has never been more pressing”. Guess what his company sells.

I could list many more.

The discourse within the marketing industry is too often poisoned by companies that are selling something to marketers. The result? Many marketers believe broad statements that they feel must be true even though the objective information states otherwise. “TV is dead” is a classic example. That we are on an unstoppable march towards “mass, one-to-one personalisation at scale” is another.

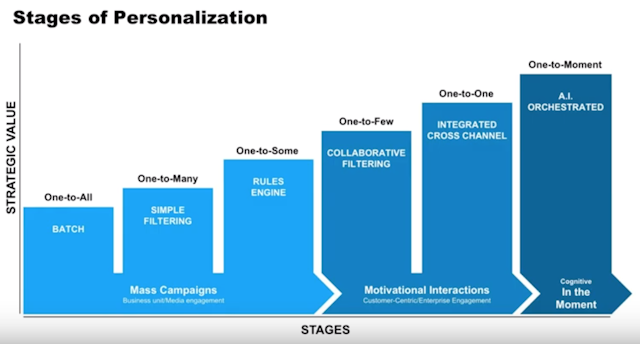

The image above is from a presentation that Sav Khetan, now the vice president of product at Tealium, gave last year stating that greater personalisation will provide greater value. And what does his company sell? A customer data platform that uses personalisation. I am Jack’s complete lack of marketing surprise.

Potentially as a result of such promotion by personalisation platforms, many marketers believe that personalisation is critical today.

“There’s also an element of marketer FOMO [fear of missing out] happening,” Neil Ripley, head of corporate communications for Comscore, told me. “With the growing consensus that a one-to-one content approach is table stakes for success, marketers are worried about falling behind and so there’s often a rush to preach personalisation, even if they haven’t yet figured out how it makes sense for their brand.”

Ignore studies from personalisation companies

One common marcom tactic today – especially in the B2B world – is to create a free survey with tools such as SurveyMonkey, get random people to respond and pretend that the results are statistically significant and meaningful. Today, whenever publicists send me such studies, I first look at the methodologies – and they are almost always shoddy.

Companies selling widgets put out ‘reports’ showing the increasing importance of widgets. But that data is rarely credible. To obtain real insights into industry trends, look not at businesses that sell products or services but at those that sell information. Such firms live and die based on the quality of their findings rather than the popularity of products or services. (And that is one reason why I rate their marketing predictions every year.)

In March 2019, the Advertising Research Foundation (ARF) in the US conducted its second annual privacy study. The findings contradict our industry’s enthusiasm for personalisation.

“People seem to understand the benefits of personalised advertising but do not value personalisation highly and do not understand the technical approaches through which it is accomplished,” the report states. “Participants did not indicate a higher likelihood of sharing data if they would receive more personalised advertising as a result.”

“Is there really more interest in personalisation today than there was a year ago? Five years ago?” ARF chief executive and president Scott McDonald said in an interview. “What’s changed is that we have more data on which to base personalisation – and more companies that can claim expertise in helping marketers on that journey.

“Are those claims credible? Are the data really good enough? Does a marketer’s investment in personalisation make economic sense, generate positive ROI and fit with the larger long-term strategy to build brand equity? Does personalisation benefit the consumer in tangible ways that overcome the liabilities of seeming creepy or of running afoul of increasingly stringent privacy regulations? These are all open questions that will be sorely tested in 2020.”

According to Gartner, personalisation efforts currently comprise roughly 14% of marketing budgets. But read just a few of the analyst firm’s predictions in a November 2019 report:

- By 2021, one-third of marketers will reduce spending on personalisation as a line item in the marketing budget and 40% of marketers still employing personalisation will prioritize digital commerce use cases over marketing, customer experience or both.

- By 2022, 50% of personalisation vendors will report lower projected revenue growth.

- By 2025, 80% of marketers who have invested in personalisation will abandon their efforts due to lack of ROI, the perils of customer data management or both.

As I mentioned in a talk in Mumbai last year, personalisation cannot occur without companies collecting and using our personal and private information in the first place. And as countless hacks have shown, nothing stored in the “cloud” – or on any computer or server that is connected to the internet – is 100% safe and secure. In 2020, companies will likely face increasing fines and court judgements over the improper collection and unsafe storage of consumer data. And that will directly affect personalisation efforts.

“The shift for brands and vendors will be to focus on first-party data access, meaning brands will need to leverage the information that they have collected on their customers with their consent,” Jenn Leire, vice president of client engagement at Analytic Partners, a New York consultancy and technology company, told me.

“Due to the California Consumer Privacy Act, brands will need to receive an individual’s consent to use their data, and customers may agree in order to receive personalised ads with products, services and discounts based on their past behaviours. In essence, brands need to make the trade-off ‘worth it’ for consumers: consent in exchange for personalised offers.

“Retailers and financial services companies are arguably in the best position to leverage their first-party data in a privacy-safe [way] to provide personalised products, services and discounts.”

Still, a March 2019 Forrester Research report highlights the problems that retailers specifically have with personalisation efforts.

“Some of the key challenges that retailers face are that they have limited data (ie only their own first-party data), they get infrequent visits even from their best customers, and their product catalogues are often small (ie a few thousand items),” the report states.

“For years, clients have asked Forrester analysts whether there are any great solutions to measuring consumer behaviour. Because few retailers have mastered this skill, personalisation continues to be a challenge. The retailers surveyed told us that the top two inhibitors to personalisation programmes are their inability to track shoppers across different touchpoints and their inability to attribute sales accurately to marketing programs when shoppers touch multiple channels.”

Personalisation is just extreme segmentation

The debate over marcom personalisation is actually a discussion about segmentation. Should marketers communicate one message to everyone, a different message to each individual or something in the middle?

Peter Weinberg, a global lead at LinkedIn’s B2B Institute, has rightly called personalisation “the worst idea in marketing”.

“You shouldn’t personalise because it’s unethical and dystopian for marketers to collect mountains of personal information about their customers,” he wrote in a post on the social network.

“You can’t personalise because most third-party data is garbage. Studies show the leading programmatic vendors can’t guess your age right 75% of the time. You wouldn’t personalise, even if you could, because all the best creative (movies, books, ads) is impersonalised [and] grounded in universal human experiences that we can all relate to and enjoy together.”

To see the power of mass messaging, just look at the recent US and UK national election results.

Quick: what was Donald Trump’s election slogan in 2016 and Boris Johnson’s in 2019? I bet everyone reading this column remembers. Now – without looking them up – what were those of Hillary Clinton and Jeremy Corbyn? I bet no one can recall. One single, powerful message communicated to all potential category buyers can win elections and build brands.

The best thing in long-term brand advertising today might simply be doing what has always been done. Craft a single striking and simple message. Communicate it creatively, emotionally and memorably. And maximise the reach as much as possible. Too much personalisation will only get in the way.

I agree with doing what Byron Sharp calls “sophisticated mass marketing” – the practice of segmenting only when absolutely necessary. Say that you sell clothes for men and women. You would create two sets of ads. Now, say that you want to segment the men and women each further into blondes, brunettes and gingers and create different ads for each gender and hair colour. You would create six sets of ads.

Segmenting by gender makes sense. Segmenting further by hair colour makes little sense and only triples your marcom cost by forcing you to create six sets of ads rather than two. Using too much segmentation and personalisation falls victim to what Sigmund Freud called the “narcissism of minor differences”. (See this interesting Twitter thread by Rouser chief executive JP Hanson for more background.)

People generally have more commonalities than differences between us, but unfortunately it is human nature to focus on what separates us rather than what unites us. Marketers should remember that fact. Instead of obsessing about numerous segments, think first about what all potential category buyers of all types have in common when it comes to your product or service. You might just need to create one advertisement that highlights that one, single thing for everyone.

Taken to its logical end, personalisation leads only to segments of one person. And the necessary technology to do “mass one-to-one personalisation at scale” is likely as much a fantasy as the Fountain of Youth, the Holy Grail or Victoria Beckham thinking she could have a prosperous solo career away from the Spice Girls.

Still, personalisation can be useful in a different context.

Product versus promotion personalisation

In 2013, Coca-Cola launched its Share a Coke campaign, which led to better consumer perceptions of Coca-Cola, Diet Coke and Coke Zero. US sales increased by 0.4% year-over-year after 11 straight years of declines. Today, people can purchase personalised bottles online. Marketers still cite this example today as something revolutionary.

But Tom Goodwin once tweeted this advertisement from The Saturday Evening Post in the US from 1953 to show – correctly – that personalisation in products has always existed. There is little new under the marketing sun.

Today, Nike By You – formerly NIKEiD – offers shoes that buyers can personalise by choosing from colour and design palettes on the company’s website (see the bottom of the right side of the above image).

Next month, Snapchat will release Bitmoji TV, a personalised cartoon programme that will include each user’s individual avatar.

Advocates of personalisation – whether through these examples or those of platforms such as Netflix and Spotify – cite product personalisation as evidence that marcom should also be personalised. But product and promotion are two extremely different things.

Much of the discussion in the marketing industry paints with too broad of a brush and ignores specific contexts. As a result, people see personalisation in products and think it should apply to promotion as well. But in general terms, people want personalised products but not personalised and targeted marcom.

The future of personalisation might actually be companies using mass messaging to sell an inventory of customised products. Nike By You’s tagline is a perfect example: “Just you, us, and a million possibilities.”

The Promotion Fix is an exclusive biweekly column for The Drum contributed by global keynote marketing speaker Samuel Scott, a former journalist, newspaper editor and director of marketing in the high-tech industry. Follow him on Twitter. Scott is based out of Tel Aviv, Israel.