An Hour of Advertising with... Quiet Storm's Trevor Robinson

Trevor Robinson OBE is a proper advertising legend. He’ll hate that I used that term. But I’m sure plenty will agree.

Trevor Robinson

He began his career at HHCL, an agency known for high-jinx, rebellion and ultimately, bloody brilliant creative work. Whilst there, he and partner Al Young created standout campaigns for the likes of Martini, Golden Wonder, Apple and, of course, Tango.

Indeed the pair’s ‘Slap’ ad – which introduced the iconic Tango man and was named as the UK’s third-best advert of all time – was perhaps the work that most typified HHCL. And it put Trevor on the map.

In 1995 Trevor broke away from HHCL to launch his own place, Quiet Storm. It was notable for being the UK’s first joint creative agency and production company and is still going strong under Trevor’s guidance almost 25 years on.

Trevor’s warm, humble and fiercely proud of his South London upbringing. He also does more than most to raise awareness of diversity and recruitment issues within the industry – in 2007 he founded Create Not Hate, exposing kids affected by gang-related violence to the opportunities of the creative industries.

The charity’s work has received international recognition. And was one of many reasons why Trevor was awarded an OBE for services to UK advertising in 2009.

But of course, even the biggest legends fuck up. Which is why we always start with the usual question…

Part one: a terrible start with Pepe Jeans, forming the industry’s most infamous creative department and the need for a Zlatan mindset…

Do you remember the first time you really fucked up?

Al (Young) and I lucked our way – well, I say it was luck, we spent a lot of time on the dole and worked bloody hard – to get into advertising, and we got into HHCL. And HHCL was Agency of the Decade at the time. It was a bunch of mavericks. Everything they were doing was really ‘anti-establishment’. Steve (Henry) and Axe (Chaldecott) were quite open about ‘hating everything typical about advertising’. They and the other founders – even Rupert (Howell) were the energy of ‘punk-rock era’ in our industry.

We were at HHCL and we had just managed to win Pepe Jeans. And Al and I had this really simple idea, where we would capture that moment when you really have a laugh with your mates. When you have hysterics for no real reason. It’s normally something you can’t really share with anybody else – so we wanted to capture the essence of sitting around in your jeans, having a laugh with your friends. That was all the idea was – to capture it in a 30-second commercial.

I’m sensing something awful is going to happen…

Well first, we had all these different straplines on it, and eventually the line ended up being ‘Pepe – because one day you’ll die’. Seriously, that’s what we ended up with. And then we couldn’t get the director we wanted. When we needed an alternative, a famous British actor turned director came up in conversation. Al and I loved him as a comedian, so Steve suggested we asked him to direct the commercial. We agreed and met with him. And at that time, let’s say he had a bit of a rock star way of living.

Our ideas differed. We wanted the ad to involve a couple of people laughing. He wanted eight people all together laughing. Being quite gullible, we sort of agreed. So we got these people in a room and we thought we should probably throat-mic them, considering how many there were. He said ‘nah, you don’t want to kill the atmosphere’. Which we also said ‘ok’ to. And it was a disaster. When we heard the sound back, it just sounded like this high-pitched, squealing sound. Like animals in a cage.

Did you know it wasn’t going to work, even at the shoot?

I remember it was a hot day and we were getting little pockets of laughter that felt real, but you could see the director was struggling with it. And afterwards he kept doing these really weird edits to try and make it work. And it just didn’t work. I think that in the end, he came to us and said, ‘I’ll be honest, none of this works, I fucked up, I’ve put some music over the top to try and make it work’. Al and I looked at each other and went ‘fucking hell, we’re going to be fired’.

Did you run with it?

In the end, we decided to individually get the same people back to laugh. But the issue was that when you laugh, your face and laugh don’t actually fit together. It was really odd and we couldn’t make it work. So then we had to get trained comedic people to laugh in order to make it work. It was awful and I thought that was already the end of us. It was so bad. I remember watching it on TV and found it hard to watch. It was a 40-second commercial and we wanted to die. We knew after that we had to do something big to survive. And luckily after that we did Tango…

That’s not a bad response! HHCL really was such an amazing agency at the time – were you conscious of just having to always hit such high standards?

Yeah. Even Steve and Axe had just done the Holsten Pils ads. They were genius, and that was just our creative directors doing some stuff on the side. All the people around us were brilliant. Dave Buonaguidi was there, Naresh (Ramchandani) was there, Liz (Whiston) and Dave (Shelton) who did all the Ronseal ads were there. Al and I knew we had to be the best team there. To do that you needed the Zlatan Ibrahimovic mindset – you had to believe you were the best.

Did that come easy?

To be honest, I just wanted to do what my family liked. My brother would come back and say ‘did you see that ad on TV, did you do that?’. I’m lucky enough to have been able to say yes a few times, but usually it was ‘no’.

Part two: initial insecurities, growing up a geek and why every creative needs a thick skin…

Was it clear when you were in a creative department like HHCL that most of you would go on to run agencies or departments?

I got that feeling, but it wasn’t necessarily completely clear. We knew that there were a bunch of maverick people – me included – that just might not function anywhere else. So though there were a lot of great people, the next step may have been for a lot to start their own thing.

Like you did?

I didn’t want to start my own thing, I never thought I was an ‘entrepreneur’ – I just wanted to get into the industry and hopefully ‘hang in there’, much less go off and run my own stuff for 25 years. It’s terrifying to think now of the balls that kid had back then to start his own agency. I’m not sure I’m that guy anymore!

What did clients think of HHCL, considering you were a load of people who didn’t like traditional advertising?

What you’ve got to remember is that you’re also looking at a bunch of people who were incredibly smart and incredibly charming. They had the amazing ability to hide that. Or at least they were able to draw into the enthusiasm of what they were doing – and I think that works well for creatives. Even though creatives can get frustrated with client feedback, they know that they need their audience, and that audience for creatives goes ‘creative director, then client, then outside world’. My audience has always been the outside world, so to get there you have to go through the process.

Is that easy to accept?

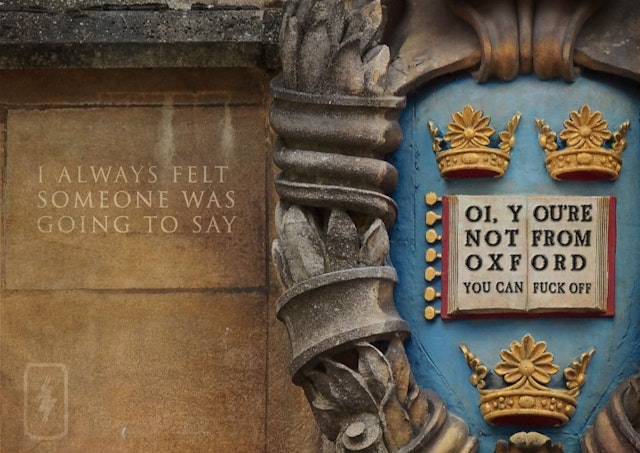

Sort of, because I always think ‘how the hell am I in advertising?’. I’m not like anyone. I always felt someone was going to kick the door in and say ‘oi, you! You’re not from Oxford, you can fuck off’. But actually I realised that really helped, because I’m more like the target audience than other people.

Was your social life very different to your working life?

Well I’ve always been into film and theatre. I remember bunking off school to go and see Blade Runner for the first time, at the National Film Theatre. None of my friends wanted to go. I remember hearing about this film that was being slated, but was also being seen as a cult movie. And I sat in a completely empty cinema, watched Blade Runner and was completely blown away. Now I’m working in the same building as Ridley Scott.

I’ve always been a bit odd. I didn’t quite fit in with the guys I grew up with, but I also didn’t quite fit in with the industry people. Even at college I remember not really getting along with people that well. And at the time I was really a bit upset about it, because I was disliked in a slightly suppressed way. Where I grew up, if someone didn’t like you, they’d just punch you in the face!

Did that happen often!?

Back home, people used to be scared of me, because my brothers were nuts. My brothers had a big gang, who I grew up with. You couldn’t mess with them, so I had this ‘bubble’ around me, even though I was there reading comics and drawing go-karts. People still wouldn’t mess with me! But no-one really ‘got on well’ with me. I used to want to hang out with the geeks. And the only time I’d get really angry was with bullies who harassed the geeks.

Will you recommend the industry to your kids?

I’d never stop them. But I’d make it really clear that if they get into it, they have to get into it on merit. So if they ask me and are passionate about it, I’ll give them advice and help them in the right way. But I’d never sit them down and say ‘right son, this whole company’s going to be yours one day. You don’t need to do anything, just come in and be a creative’. I’m afraid it’s not that simple.

If you ain’t got it, you ain’t got it. And I’ve seen that happen. You’ve got people who should have everything, but they just can’t translate that to the industry. You can’t work out why, but it happens. It’s like those footballers who you see in the playground who have all the skills but never make it further because they don’t have ‘it’.

Is it a work ethic issue? What are the emotional qualities you really need in this industry?

I can’t speak for other people on whether it’s work ethic, so I don’t know. But what I’ve seen is that in this industry, you have to be absolutely driven and tenacious. And be willing to take knockbacks and not be fragile when they come. Because they will come. Even at our height at HHCL, we had people slag us off. They would say we were passed it and our best work was all behind us. They’d be nice to your face but have a go at you behind your back. You have to be prepared for that.

Part three: life after Tango, a ‘shambolic’ start to Quiet Storm and the fear of presenting…

Did you find attitudes towards you changed when Tango came along and you had that amazing run of doing great work?

Yes, they did. But the main thing is that, after Tango, we changed too. Because we became arseholes. We were able to get cabs everywhere, we’d walk into rooms and people would say to each other ‘look, it’s Trev and Al’. It wasn’t for a long period, but in our tiny little world of advertising, it was like we became stars. You’d go to award dos and people would break off conversations to chat with you. I’ve seen it with others too, where people do successful campaigns and everyone else treats them differently.

You have to become aware when it’s happening, and you have to work really hard to make sure you don’t become a nob. And I did, for a bit, become a bit of a dick. I had to realise it and say ‘look, that’s not me’. It’s ridiculous really because we only work in advertising, for fuck's sake.

When you started Quiet Storm, there was a clear proposition, but were you conscious of the ‘attitude’ of the agency, and how it presented itself?

I’ve got to confess, it was a shambles. There were four of us who left HHCL. There was me, Al, my ex-wife – she looked after the finances, because I was shit at that. I mean really shit – I’m lucky I work with my second wife now because I need someone I can trust, and I mean really trust, to look after that front. If I looked after any of that we’d be dissolved within two days. I don’t even open my mail or know where I’m meant to be. My kids can’t understand how many unread emails I have.

Then the other person we left HHCL with was our producer, Jane, but last minute she pulled out [and] we’d already told Campaign that it was happening – I think we even got a picture of the four of us.

Al then decided to go back to HHCL, so it was just me and my ex-wife. No clients. No real vision. I don’t know what the fuck I was thinking! But I knew that I liked writing and directing, and I thought at the time I’d done enough pieces of work that people would know that this wasn’t just a little guy with no record.

So how did those first few months go?

I was lucky that there were a lot of creatives who liked me as a director, so early on I was directing a lot of other creatives’ work, so 90% of Quiet Storm’s early work was as a production company.

It was only after a few months that I started getting some more grown-up people in. I had some planners and account people join. And gradually a business started to develop.

But if I was to ask you then to see a business plan…

Ha, no chance mate. I’m always envious of these guys who have their serious well-drawn plans and new business machines whirring from the start. I had to resort to cold-calling, and wow it’s the worst, most painful thing I’ve ever done. I had to do that, I had to do everything. And I wasn’t cut out for it.

You’ve certainly built something now though, so it can’t have been all bad…

And do you know what, it actually helped me a lot, because it taught me so much. I do talks and other things now that I do better because I had to learn on my feet back then. I still don’t present my own work – because my dyslexia and other issues take over. I can’t read a script out loud. Honestly. I get panic attacks.

But it taught me that I could hold my own. If you told me that I would end up not being bad at presenting, I’d have told you to fuck off. If you’d have told Al that, he wouldn’t have believed you, because he had to present all our stuff for me.

That’s commitment from Al!...

We actually went up to John Hegarty years ago to try and get in at BBH. It was at some champagne breakfast thing that we gatecrashed. We were on the dole and we saw John Hegarty and Dave Buonaguidi in there. So we split up – Al’s job was to speak to John Hegarty and mine was to speak to Dave. I spoke to Dave and he got us in at HHCL, because he went back to the agency and told them that he’d spoken to these two weird guys and they should look at our book. And when Al went up to John Hegarty, he was so nervous that he couldn’t say anything, and John literally just walked away!

Part four: Quiet Storm as a launchpad for creatives, the industry’s diversity problem and sustaining success for 25 years…

Quiet Storm has been a bit of a platform for launching the careers of other people. Is that really important to you?

That’s one of the things that I don’t really talk about, but it really does give me a kick. I see Jo (Wallace) now creative director at JWT, I see some amazing directors – I did this whole thing around knife crime years ago, and a young director, Dennis Gyamfi, who we did it with, is now working with Idris Elba. So when you’ve been involved with helping people move their careers forward, it feels really good.

I think that comes as well because I can’t really remember too many people helping me out. Obviously, there were some and they were really key – I’ve already mentioned Dave Buonaguidi – but back then so many people were wrapped up in their own careers. And I always think that you get such a reward by helping people when they’re smart and talented and then they go and fulfil that potential. I’m always really proud.

I’ve got this producer friend, Nancy, who used to work on our reception. And she said to me, ‘I’d never have made it without your help’. And I’m thinking ‘bollocks, you would have done’. But at the same time, if you can help people, then it is a real buzz.

When it comes to bringing more diversity into the industry, do you still feel that it’s mainly talk and not a lot of action?

Yeah. I can never understand it. A lot of people want to do good and say they’ll do good, but invariably they’ll just hire someone like themselves again and again. Because they know what those people are thinking, they know where they’re going, and if they’re honest, they’re happier with that. No one really wants to say that they hired somebody ‘on paper’, it always comes down to the gut.

I’ve always got on well with women in business. Because I’m quite emotional and I’ll talk on an emotive level. And men don’t really want to do that – they’ll posture and say ‘let’s talk about football’. I always had that even when I was a kid – I always hung out with my older sister and my older sister’s friends and just chatted and listened to their stories. Some of them were a bit disturbing for a kid that age! But I used to find that far more interesting and stimulating. Because the conversations were much more honest.

That’s the same in advertising. You meet people you know and can have conversations like we’re having now, but then you meet someone else you know and when you try a similar conversation, they look at you like you’re strange. You think things have moved along and then you realise things really haven’t.

So finally, you’ve been running Quiet Storm for 25 years now. Especially considering that it clearly wasn’t the plan, how do you keep an agency going that long?

It boils down to two things for me. One is the obvious thing, which is that working with young people has really rejuvenated me. This should be fun. We’ve got a great bed of clients and a load of people working at the office who I really, really like. I’d go for a drink with them – if they wanted a weird old bloke hanging around!

The other thing is that I’ve never really thought that I’ve arrived. It’s easy to get caught up with your own and other people’s achievements. I’ve never allowed myself to do that and it keeps me on my toes. Don’t get me wrong, I’ve got a great life. A great place to work, lovely house, lovely wife, brilliant kids, we can holiday pretty much anywhere we want. But we don’t take it for granted.

Why do you think that is?

I think it boils down to your beginnings. I’ve never really had a sense of entitlement or security around money. Some people come from money, and they will always have money. I think it’s a cultural thing as much as anything. You become a doctor because you believe you can become a doctor. Because your dad was a doctor and your grandfather was a doctor. It’s the same thing with money. And for me there’s always a feeling that it might all go horribly wrong and I could lose it all tomorrow. So, my energy level is always up.

Well, I don’t think I could ever fall that badly, because I’ve already risen far higher than I ever thought I would. But there is still that fear that if I’m not useful anymore, I can’t retire. Plus if I did retire, I’d be bored shitless. I think I’d be dead in a month! I’m not the kind of person who wants to sit around on a beach until I fall face down into the sand.

Artwork by Guy Sexty

For more from the Hour of Advertising series, click here