‘Growth hacking’ is a long con that will only lose you millions

If you have to ask the bank for a loan every year to stay in business, you are not running a successful company. The same is true if the bank is a VC investor.

In recent years, the term ‘growth hacking’ has become popular in the high-tech world. But is it the best approach? Let’s compare growth hacking to what I will call ‘marketing’ in terms of what builds the most profitable companies over time.

What is growth hacking?

“Growth” can refer to an increase in anything. Revenue. Customers. Employees. Profits. The number of workers who love Spandau Ballet. Ryan Holiday, the former director of marketing for American Apparel who is now an author and media columnist for the New York Observer, specifically put it this way in his 2013 book Growth Hacker Marketing:

“While their marketing brethren chase vague notions like ‘branding’ and ‘mind share’, growth hackers relentlessly pursue users and growth… whereas marketing was once brand-based, with growth hacking it becomes metric- and ROI-driven.”

Immediately, I have a problem. As I wrote last year in the context of the forthcoming post-GDPR world, not everything that is important in marketing can be measured and not everything that can be measured is important. Moreover, many digital metrics are incomplete or completely inaccurate. Not every activity in marketing can or should aim to receive an immediate, trackable response.

But for this column, I will address another point: The word ‘profit’ does not appear in Holiday’s definition. “Growth,” in other words, is a focus on top-line results at the expense of everything else. And we will see where that leads.

No need for profit?

In Disrupted: My Misadventure in the Start-Up Bubble, Dan Lyons, a former technology editor at Newsweek who moved into the startup world, describes how the tech world have changed over the past few decades:

“The biggest difference between today’s tech start-ups and those of the pre-Internet era is that the old guard companies, like Microsoft and Lotus Development, generated massive profits almost from the beginning, while today many tech companies lose enormous amounts of money for years on end, even after they go public...

“Suddenly, there was a new business model: Grow fast, lost money, go public. That model persists today… The company is buying one-dollar bills and selling them for seventy-five cents, but it doesn’t matter because mom-and-pop investors are looking only at the revenue growth rate. They have been told that if a company can just grow big enough, fast enough, eventually profits will arrive. Only sometimes they don’t.”

According to a report last week in The Wall Street Journal, WeWork’s revenue last year was $866m but expenses were $933m. As stated in the article, WeWork’s company filings also reported a so-called “community-adjusted EBITDA” that removed interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization as well as marketing, administrative, development, and design expenses to report positive earnings of $233m.

In this column, I usually report on marketing bullshit. I had never encountered accounting bullshit before.

Twitter user Downtown Josh Brown described WeWork’s statement perfectly: “Before all costs and expenses, we’re very profitable.” It is little surprise that the company had to raise $702m by selling bonds last week as well.

It does not stop with WeWork

To be fair to WeWork, it’s not unusual to have both growth and losses.

For this column, I contacted several martech companies of various types and sizes to learn about their approaches to top-level versus bottom-line results. In alphabetical order, I looked at Buffer, HubSpot, Klear, Moz, Outbrain, and Taboola. Several of them, to varying degrees, seem to have used or advocated for growth hacking.

Such businesses are always happy to highlight their revenues, but they rarely discuss net profits. I asked for that information. Here is a summary of the financials - when I was able to get them.

Buffer

Buffer, a social media sharing tool, publicly releases financial data here. However, the information does not list net profit. I contacted the company, and they shared with me their EBITDA figures. Total 2017 EBITDA: $2.78m. Q1 2018 EBITDA: $1.18m. The company is profitable.

Buffer executives told me that they were interested in discussing their approach to profitability for this column, but they were unable to send a comment before my deadline.

HubSpot

I reviewed the historic financial result of HubSpot, an inbound marketing platform, in this prior column showing that the company has had increasing net losses since at least 2012 despite growing revenue.

A HubSpot spokesperson did not respond to my request for comment on the company’s unprofitability.

Klear

Klear, an influencer marketing platform, shared the following EBITDA numbers with me: $800k for all of 2017 and $900k in Q1 of 2018.

“The importance of profitability at Klear is a big part of our company values. We believe it drives of excellence in the company as a whole,” Klear COO Guy Avigdor said. “Measuring sustainability requires us to be extremely focused on providing real value and a superior solution.

“Many entrepreneurs don't consider this path as often as they should. When the top-line metric is profitability, each decision is measured by the return on the team’s time investment. For instance, the product team won't push a complicated feature to close one singular deal. When you have such a lighthouse, these decisions become much easier to get right, with less internal friction.”

Moz

Moz, an SEO software tool, discloses annual financial performance on the company’s blog. For 2017, the company reported a positive EBITDA of $5.7m. That figure for the preceding three years was negative each time at $5.5m, $3.1m, and $2.1m.

Moz CEO Sarah Bird declined to comment for this column.

Outbrain and Taboola

Ad tech platform Outbrain has revenue, in one estimate, of $42m per year. The same figure for Taboola, a similar company, is $208m per year.

Both companies declined to comment on their profits for this column.

The long con

As some of these companies may show in the future, the “growth hacking” phenomenon is a long con that benefits VCs who invest other peoples’ money in tech startups, convince the world that rapid growth without profits is a good thing, promote their companies that show that result, get rich at IPOs, and leave post-IPO investors holding the bag.

Look at FitBit. FitBit’s 2015 IPO opened at $20, but the company’s losses have finally caught up to it. The company’s net profit in 2017 was negative $277m, and the stock was trading at $5.30 when I filed this column. Look at GoPro. The company’s 2014 IPO was at $24. Net profit last year was negative $183m, and the stock was trading at $4.88.

Many large tech companies that are lauded for their growth have little or non-existent profits as well. Elon Musk’s Tesla is expected to post huge losses this week. People other than investors rarely benefit as much from the long con. (For more information, see this earlier column of mine on the realities of the startup world.)

Unprofitability will always catch up to you - and many founders and investors aim to cash out before that happens and leave someone else holding the bankrupt bag. It is VC math compared to real math. Growth hacking increases users and revenue rather than profit.

The more that a company highlights top-line growth, the more likely it is that the business is trying to hide bottom-line results.

After all, there are only two exit possibilities in the growth mentality: Get acquired by an enterprise company that can eat the losses, or do an IPO and convince the masses to buy shares based on revenue growth and take advantage of their lack of business education.

When there is another major recession - and there is always another one just around the corner - these companies will be the first to fall.

Growth hacking does not work

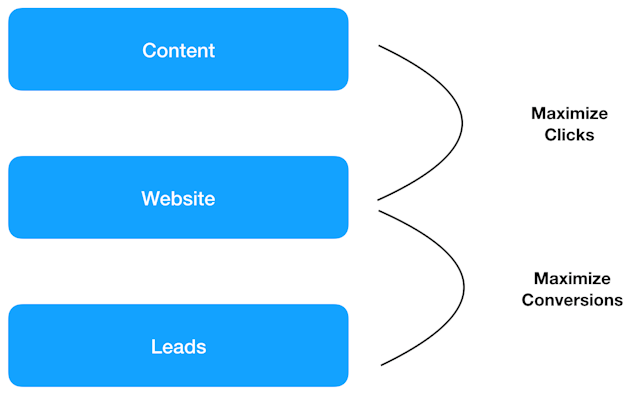

Here is a summary graphic that I created to describe the specific marcom process in “growth hacking”:

In line with Holiday’s definition, the goal is to spread whatever “content” over the internet will maximize clicks to a website from a relevant target market and then maximize the website’s conversion rate of the traffic into sales or leads. This two-pronged approach is constantly tested and optimized in an “agile” way with various tools, metrics, and dashboards.

Sure, it sounds reasonable. But it is usually a long-term waste of money.

Matt Arbon, the creative partner at the Sydney advertising agency ScienceFiction, wrote the perfect response in this tweet:

“The digital age has ushered in the illusion of effectiveness where we’re choosing advertising approaches that have more to do with easier and instant-gratification measurement than advertising that actually works in the long term.”

That instant gratification is sometimes in the form of clickbait headlines that push psychological buttons to get people to click. But all clicks are not created equal. At one prior job, a client wanted to publish and disseminate clickbait blog posts. Sure, the material received a lot of clicks - but it resulted in far fewer sales and lower conversion rates than posts with headlines and information that were, shall we say, less sensational and more credible.

The reason? It comes down to signaling. Publishing clickbait might get clicks, but it subconsciously signals that your brand is low-quality. That is why so few clicks translate into sales. Publishing clickbait to maximize growth is akin to beating people over the head and dragging them into your store. Sure, they entered the store - but they will not buy anything.

And what works in the long term? Here is a chart from IPA in the UK’s recent PDF collection of The Greatest Hits of Les Binet and Peter Field:

To maximize long-term profitability, the same thing is true today as it was before the internet: allocate roughly 40% of your spend to short-term activation and 60% to long-term brand building. But growth hackers never think of the second part. And that is why their activities rarely lead to profits over the long run.

Celebrating growing revenue while ignoring increasing net losses is as ludicrous as getting a $1m loan from the bank and then proclaiming that you are rich. It makes as much sense as as the video for Bonnie Tyler’s 1983 song Total Eclipse of the Heart.

And it’s full of buzzwords

Half of growth hacking is the use of tactics that do not work in the long-term. The other half is just traditional marketing repackaged into a new buzzword so that it seems that the idea is something new.

Just see Marketoonist Tom Fishburne’s humorous take:

The benefits of real marketing

I have never understood why startups celebrate funding rounds. It means little more than share dilution and selling off percentages of companies that founders and employees have built through their hard work.

The growth hacker model is this: Spend all your money to gain as many users and as much revenue as possible. Get a bigger round of funding to do much more of the same thing for another year. Rinse and repeat on an annual basis through the Series A, B, C, and so on until you are acquired by another company or do an IPO.

But here is the catch: If you do not get more funding in a particular year, your company is bankrupt because you have had no profits.

In the words of Andy Budd - the CEO of strategic design consultancy Clearleft and cofounder of DigitalBrighton in the UK - I recommend doing what he calls 'sloth hacking' instead:

“Sloth hacking - the opposite of growth hacking. A focus on slow and sustainable growth based on generating real user value, rather than the deployment of psychological tricks and techniques.”

Or, you know, doing real marketing and proper business planning. Focus on net profits instead of revenue. Put a percentage of each month or quarter’s profit into retained earnings (the business version of a personal savings account) for rainy days. Instead of relying on loans or investors to bail out your sinking boat each year, build and sail a sturdy ship in the first place.

Otherwise, you will end up like WeWork and the on-demand shipping startup Shyp, which recently shut down despite obtaining a $250m valuation in 2015. “Growth at all costs is a dangerous trap that many startups fall into, mine included,” the company’s CEO, Kevin Gibbon, wrote in March.

Do not hire “ninjas” and “rock stars” to do growth “hacks.” (If I call a plumber and he does a "hack" job, it was a quick, crap job that still left the underlying problem.) Bring on board professional marketers who know how to do the necessary customer-facing research to create a marketing and communications strategy that will be profitable for the short- and long-term. (Of course, that strategy will be different for every company and product.)

Growth hackers, you can’t always get what you want. But if you try sometimes, you might find that you get the traditional marketing that you need.

The benefit is the founders and employees will build a real company and not dilute their percentages of ownership in favor of investors. And they will not be under constant investor pressure to deliver short-term results that harm the business in the long-term.

As someone who at one point in my career was the first director of marketing at a high-tech startup that has become successful, I certainly understand that many companies need to find investors or remain in debt while a product is created and early customers are gained. But every company that is worth a damn should become profitable at some point.

If you use growth hacking to gain more and more customers and revenue but are losing more and more money every year, you are merely building a bigger house of cards. That unrestrained growth will eventually kill the host. Just like cancer.

The Promotion Fix is an exclusive biweekly column for The Drum contributed by global marketing and technology keynote speaker Samuel Scott, a former journalist, consultant and director of marketing in the high-tech industry. Follow him on Twitter and Facebook. Scott is based out of Tel Aviv, Israel.