From the NHS hack to BA’s IT meltdown, history will keep repeating itself until brands prepare properly

As soon as any disaster strikes, history dictates that media coverage follows the same pattern. Experts are wheeled out to speculate on what happened – could it have been prevented, who is to blame and how can it be avoided in the future?

Media coverage of the cyberattack on the NHS followed this pattern. Whether the lapse was due to complacency, ignorance or simply a lack of money, the cyberattack on the NHS was one hell of a wake-up call for all concerned.

With scores of hospitals and GP surgeries locked out of their computer systems, there was immediate panic amongst staff and patients. Appointments and operations were cancelled as large parts of the NHS were crippled.

The cyberattack story was a Godsend for the international media. Newspapers, television and radio around the globe rolled out their experts and gave top billing to the computer meltdown affecting 20,000 devices across 150 countries.

Patients turned away as they arrived for hospital appointments were interviewed – many in tears. GPs who had been forced to cancel hundreds of visits and hospital administrators explained how they had reverted to recording treatment on paper.

Techies were given airtime and column inches explaining the intricacies of high-level hacking. And praise was given to a 22-year-old cyber-security expert, Marcus Hutchings, who inadvertently managed to find a “kill switch” that slowed the global rampage.

Hutchings is already regretting his raised profile, however. He tweeted: “I knew 5 minutes of fame would be horrible but honestly I misjudge(d) just how horrible…British tabloids are super invasive.”

On the mark, Marcus!

The finger of suspicion has been pointed at cyber criminals in China and North Korea for launching the ransomware, which in a few hours infected victims in at least 74 countries including Russia, Turkey, Germany, Vietnam, and the Philippines – and is thought to have spread at a rate of five million emails per hour.

Ransomware attacks are not new, but the speed of the recent hackings has alarmed security experts. The first known ransomware attack, dubbed AIDS Trojan, happened in 1989. It was ultimately unsuccessful because few people used personal computers at the time, and the internet was mostly used by science and technology experts. Also, international payments weren't as common back then.

Fast forward to today: a huge amount of data is regularly stored on computers, people are connected to the internet via an array of devices, and sending money internationally takes little more than a swipe and a tap.

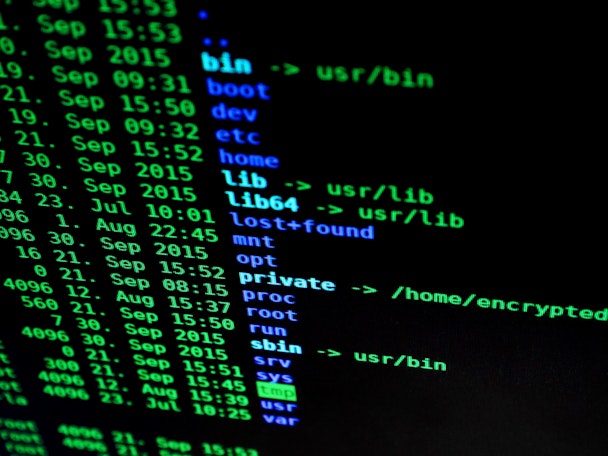

The attack, which exploited a known vulnerability in out-of-date Microsoft Windows operating system, is known as the WannaCry virus and affected Telefonica in Spain, FedEx in the US and Renault, the car manufacturer.

The main reason medical institutions and the NHS were targeted is because they have vast amounts of patient data at their disposal.

Jean-Frederic Karcher, head of security at Maintel, said: “Medical information can be worth 10 times more than credit card numbers on the deep web.

“Fraudsters can use this data to create fake IDs to buy medical equipment or drugs, or combine a patient number with a false provider number and file fictional claims with insurers.”

Hackers often demand the victim pay ransom money to access their files or remove harmful programmes. The criminals behind the NHS attack demanded $300 in bitcoins to unlock computer systems.

Recently a hacking group released passwords to a range of US National Security Agency hacking tools used by the agency to exploit a weakness in Microsoft to hack into the computers of spies and terrorists.

When details of the bug were leaked, many security researchers predicted it would lead to the creation of self-starting ransomware worms. It may, then, have taken only a couple of months for malicious hackers to make good on that prediction.

However, Microsoft issued a free patch for the weakness, mainly affecting operating systems, like Windows XP, which the company stopped supporting some time ago.

Hours after news of the cyberattacks broke, a Microsoft spokesman revealed that customers who were running the company's free antivirus software and who had enabled Windows updates were 'protected' from the attack.

It raises questions about why NHS computers using the operating system were not shielded from the ransomware.

The Department of Health says it passed on the information to all NHS trusts, but, for whatever reason, some 51 medical facilities in England and Scotland failed to update their systems.

Perhaps this is because the NHS is under such enormous pressure, both politically and practically, that the DoH instruction was not seen as an immediate and compelling priority: staffing levels, keeping to government waiting times and the problems of bed blocking being seen as more important.

Or could it simply have been that large organisations have to test that security patches issued by the provider of their operating systems will not interfere with the running of their networks before they are applied, which can delay them being installed quickly.

Whatever the reason, the NHS and others, hopefully, will take note and immediate action when they receive a systems update in future.

Everyone knows that history repeats itself; it seems, however, that few lessons are learnt. As with burglaries, we are constantly told to expect another attack – a common practice being companies apparently offering protection when in fact they merely provide another virus.

Even those who have been living under a rock would be aware of the risks of hacks given the huge amount of ink spilt on coverage including accusations of cyberattacks and interference in US and French elections.

British political parties apparently approached the surveillance agency GCHQ for advice on beefing up their internet security after a cyberattack during the 2015 UK general election and the hacking in the US last year of the Democratic party.

The risk of such attacks has been widely known by NHS for some time. Back in August 2016 it was revealed that 97% of NHS Trusts had been attacked by ransomware in the preceding 12 months.

Politicians also wasted no time capitalising on the NHS’s misery.

The cyberattack provided more political ammunition on the election trail with unions and politicians slamming the underfunded NHS computer systems as experts say the attack should have been prevented.

Defence secretary Michael Fallon pointed out that hospital trusts were repeatedly warned about cyber threats before the attack on computer systems.

He told BBC One's Andrew Marr Show that the NHS was given "a large chunk" of money to improve its security.

Jeremy Corbyn, Labour leader for the next few days, said that an annual £5.5m deal with Microsoft to protect NHS devices had been renewed in 2014 but not since.

Even UKIP's Suzanne Evans managed to boost her media profile by leading calls for cyber attackers to face 'full force of the law'

History will repeat itself...

BA clearly has not learnt from either the Wannacry disaster or the United "not enough seating time for a beating" PR fiasco.

Failure to have a backup alternative to its IT system will cost millions. In addition to compensation claims estimated to be in the £150m region, the firm's owner, International Airlines Group, saw shares 1.4% down after 75,000 passengers were hit by the crisis. BA's IT meltdown chaos led to it losing £500m in value in just eight minutes.

Coupled with the disastrous handling of the crisis with misinformation and lack of communication, any PR benefits from United's woes must surely be obliterated.

BA's BS will cost it dearly and could have been avoided if lessons from history had been learnt.

...and guess what? It will happen again and again and again as brands pay lip service to measures that should be taken whilst ignoring them.

Each and every brand must have a crisis management plan in place. I always recommend that all companies should carry out regular health checks

Fail to plan and you plan to fail.

On the IT front, the advice remains the same: prevention is so much better than cure.

Backup regularly.

Be cautious about unsolicited emails and attachments.

Never pay a ransom.

Don’t rely on your IT infrastructure – it will fail…

…and be prepared for it all to happen again very soon…

Rinse and repeat….

If there are particular stories you feel should be subjected to a pressure test to find out whether they really stand up to serious scrutiny get in touch.