The public apology is in a sorry state

When is an apology not an apology? When it is someone else’s fault obviously.

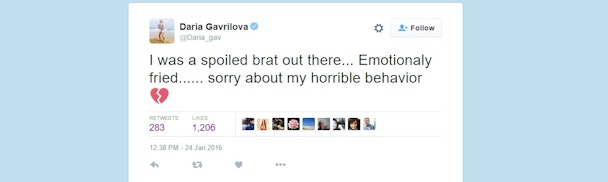

A real apology at last? Tennis star Daria Gavrilova's heartfelt tweet

Barely a week goes by that we don’t find some public figure apologising for something that they have said or done. In a world of social media, when the public can instantly express their outrage at something that someone has said, these people can be in no doubt of the need to express their regret and get their public 'brand' back on track.

What we find though is that the vast majority of these apologies appear to have been coached by the same publicist, and that that publicist doesn’t really understand what an apology is supposed to be or do.

An apology is supposed to do four things.

1. Make the injured parties feel better about the offence or injury that was caused.

2. Demonstrate an appropriate level of remorse.

3. Persuade people that the perpetrator understands why they were wrong (and by inference is less likely to commit the same offence/make the same mistake in the future) in order to…

4. ...make it possible to be forgiven.

My four-year-old daughter understands this; I don’t know why it is so difficult for people in the public eye.

If you think of people as brands then there are important reasons why all of these are necessary.

The first is to try to offset the immediate negative sentiment around your brand that has developed as a result of your action and salvage the equity that you have built until then.

The second is that if you want people to buy into you in the future they need to forgive you for the past and believe that you have understood why your action was wrong.

I believe that a compelling and sincere apology can (in some situations) actually do more good than the original offence did harm whilst a bad apology can make the original offence worse, yet the vast majority of public apologies are pretty sorry efforts.

Most (media trained) apologies go something like this: “I am deeply sorry that lots of people are upset at me. My intention was never to cause harm/offence. I am sorry that people have misconstrued my actions/words and have become offended.”

Here are a few recent examples:

Actress Julie Delpy recently upset the African American community by suggesting that women face a tougher time in Hollywood than African Americans. Her apology? "I’m very sorry for how I expressed myself, it was never meant to diminish the injustice done to African American artists … I’m so sorry for this unfortunate misunderstanding, people who know me, know very well that I can’t stand inequality and injustice of any kind."

At no point does Delpy say "I was wrong". In fact she essentially suggests that other people were wrong for misunderstanding her.

Boxer Tyson Fury felt the ire of most of the country following a wide array of distasteful homophobic and sexist comments which came to light when he received a Sports Personality of the Year nomination. His 'apology': "I’ve said a lot of stuff in the past and none of it with intentions to hurt anybody. It's all very tongue in cheek, it’s all fun and games to me… If I’ve said anything in the past that’s hurt anybody, I apologise."

Again, there is no suggestion that he accepts that the opinions he expressed were wrong or that it was understandable that people were upset or even that he would change his ways in the future, just a suggestion that the country needs to get a sense of humour.

Chris Gayle (West Indies cricketer) after being fined for making suggestive comments to TV presenter Mel McClaughlin: "There wasn't anything meant to be disrespectful or offensive to Mel. If she felt that way, I'm really sorry for that." So the only thing he is sorry for is Mel's actions, not his own.

This typical media apology is so well recognised that Ricky Gervais decided to publish a fake advance apology for the offence he was going to cause in his upcoming hosting of the Golden Globes.

Because I can see the future, I'd like to apologise now for the things I said at next week's Golden Globes. I was drunk & didn't give a fuck

— Ricky Gervais (@rickygervais) January 1, 2016

These kind of apologies fail to achieve any of the objectives of a true apology:

They cannot make the victim feel any better as they are just being told – "I'm sorry you are so sensitive."

They don’t express any remorse for the action taken – they are simply upset because they got busted.

There is no suggestion that they have learned from the incident because they are not ever really accepting fault.

I believe that a true apology could do a huge amount of good for the personal brand of the apologiser, but until recently I couldn’t find a decent example of that happening. So I’m very grateful to the young Australian tennis player Daria Gavrilova. She managed to actually break Australian hearts a little bit with her heartfelt apology for an on-court meltdown during her recent defeat at the Australian open:

"Yeah, it wasn't great and I'm very disappointed with myself. I was being a little girl… I was getting angry with myself, just showing way too much emotion. It's not acceptable. I don't know why I did that… I was terrible. I mean, I played good. But the behaviour, I've just got to learn from it."

This is a real apology, it is spontaneous, she accepts she was wrong, she shows genuine remorse and demonstrates a quality of character that makes us believe she will learn from it in the future. And do you know what? People forgave her and even supported her wholeheartedly:

.@Daria_gav it's called #experience you live and learn and get better and stronger by it. Don't forget it was your best week ever!

— Todd Woodbridge (@toddwoodbridge) January 24, 2016

Really nice to see @Daria_gav apologise for her behaviour in rd 4 Some things happen in the moment Always a fan of the humble ones #AusOpen — Robert Herrick (@robert_herrick) January 24, 2016@Daria_gav you had a great event bringing terrific energy & fun. This is an emotional journey to try to be the best you can be. Live & learn

— Pam Shriver (@PHShriver) January 24, 2016

@Daria_gav chin up dash we all make mistakes but it takes courage to own them. #respect — peter luczak (@PeterLuczak) January 24, 2016By genuinely being sorry and showing it without reservation, she appears to have almost improved her reputation rather than damaging it. We all know that we all make mistakes and we want to forgive people when they get things wrong – all it needs is a genuine apology. If only more people and brands could learn how to do this properly.

Dan Plant is group strategy director and real-time planning director at MEC