Advertisement

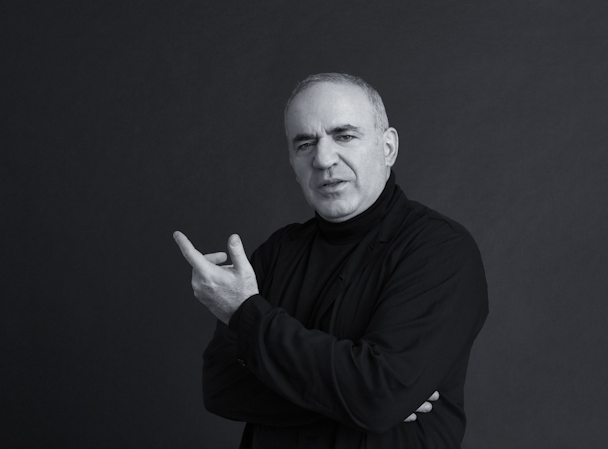

Garry Kasparov, world chess champion, is launching a new chess playing portal with Vivendi

After spending years selling chess to the global public, Garry Kasparov is now marketing his own digital platform amid a surge in popularity for the sport.

Garry Kasparov calls himself “the first knowledge worker to have their job threatened by a machine”. He’s not bitter, however. “We shouldn’t cry over spilled milk.”

The grandmaster and former World Chess Champion is talking to The Drum from New York, where he has lived in exile from Russia since 2013. Our conversation takes in the future of artificial intelligence – the game-playing kind and the kind that might put us all out of a job – as well as the future of chess.

Amid a resurgence of interest in the latter, he has been launching a new chess platform – a passion project years in the making – and before the interview starts, has some questions of his own: “Do you play? And if yes, how good are you?”

I confess to my mediocrity and admit that I spent the hour prior to our call being dispatched with ease by AI opponents on Kasparovchess, the veteran player’s new online gaming venture. “We all lose against computers,” he reassures me. “These days, it’s not something to be ashamed of!”

Alongside current world champion Magnus Carlson and former world champion Viswanathan Anand, Kasparov is one of the chess world’s major statesmen. Having retired from professional play in 2005, he has spent much of his life selling the sport to the public. And now, with Kasparovchess, he hopes to compete against incumbent online chess platforms and build on the game’s current popularity.

This is his second attempt, having launched an earlier iteration in 1999. “It didn’t go well because the technology was not there to support my ambitions of promoting chess for a global audience, and of creating something that would be financially sustainable.” The relaunched platform, made by Vivendi subsidiary Keysquare, is available via a website and iPhone app and offers puzzles, tutorials, articles and documentaries to subscribers, while limited content is available to non-paying users.

Aimed at both seasoned and rookie players, he hopes it can fill a gap in the market for chess content with high production values and a social element provided by a dedicated Discord server. “That is a key component. It is entertainment, education and community.

“I always wanted to make sure that our contribution to global chess and to our audience would concentrate on educational and entertaining elements. But I also wanted to make sure that we created a global community – that people join our platform and feel a sense of belonging.”

It also, of course, has its own playing platform for pitting your wits against other players and its AI.

Playing, and occasionally being bested by, computers is something Kasparov knows all about, having famously lost to IBM’s Deep Blue in 1997 when he was World Chess Champion.

His playing career was already entwined with the earliest days of AI and modern computing and as far back as the 80s, he was involved with some of the first attempts to bring computers into the sport, including early database website ChessBase. In 1989, he had seen off Deep Blue’s predecessor, Deep Thought.

“It was probably my blessing that I was the world champion at the time of the most revolutionary changes in the game. What happened during the 15 years of my reign changed the nature of chess – not because of me, but I knew it was happening. I saw the computers coming in, I gave the idea to my friends in Germany to do ChessBase. That was the beginning of this kind of merger between chess and computers.”

In the years since his match against Deep Blue, he has become an ambassador for AI, working with security firm Avast and giving TED talks arguing that human and machine intelligence should complement each other, rather than compete. “I’ve been preaching human-machine collaboration, simply saying ‘if you can’t beat them, join them’.

“Naturally, I didn’t feel well after the [Deep Blue] match in 1997. But now, nearly a quarter century later, I think it was it was a blessing that I was part of this experiment.”

Rather than feel threatened by the increasing use of AI across business and industry, he suggests we should embrace new, emerging opportunities. “It wasn’t the end of the world – to the contrary, it was the beginning of a brave new world.

“We could actually move forward if we stopped worrying about killer robots and recognized that evil, unfortunately, is still a human monopoly... the danger is not killer robots but the people who control them.”

The proliferation of commercial AI will serve to highlight true genius, he argues. “It is important for us to recognize that we still have our advantages, based on human-exclusive abilities. Human creativity is not a phantom, it’s a real thing.”

The royal game is more popular now than it has been for years. Kasparov credits the web, the youthfulness of current World Chess Champion Carlson and recent Netflix smash The Queen’s Gambit as each playing a role – even if the game doesn’t occupy the same space in the imagination of the public or the press as it did during the Cold War.

“When you look backward to 1972, the Fischer-Spassky match, or my matches with [Boris] Karpov in the 80s, chess often made it to the front page of a newspaper. That was a really big deal. But the main reason why it was there is that the competition for public attention was meagre.

“Chess grew in size... maybe 1,000 times since 1972. The problem is the rest of the field grew a million times. So that’s why it occupies a much smaller space.”

He jokes that his consultancy work on the Netflix show (he advised on everything from actors’ body language to the way they held pieces, as well as plotting out the moves in the matches shown) has made him almost as famous as his playing career. “For so many years, people introduced me as ‘the first man to lose to a computer’. That is gradually being replaced by ‘the consultant on The Queen’s Gambit’.”

The show, he says, reminded viewers that chess could be a mindful activity, refuting the game’s association with mental illness. Efforts to popularize the game faced “certain psychological obstacles that were the result of public perception based on images of the game that have been developed over decades,” he says.

“Let’s be honest, the great literature didn’t help much. And stories of Bobby Fischer didn’t help demonstrate that chess could keep you sane and not potentially endanger your mental health.”

Thanks to The Queen’s Gambit, however, people have changed the image of the game in their mind. “It’s no longer seen as a potentially destroying their kids or endangering their mental stability. To the contrary, it’s seen as kind of a test that can help them overcome certain character traits, like the story of [protagonist] Beth Harmon overcoming a dependence on drugs and alcohol. The image of the game has risen dramatically.”

The show’s impact, he says, proves that people want personality with their chess content. “Every story that you sell, every lesson you do, it should carry this element of personality, because that’s what people want to hear. It’s not, ‘Oh, this is the right move.’ Instead, it’s ‘When I was a kid, I made this move because...’ This way of addressing the audience will hopefully be our signature.”

Kasparov hopes his own personality combined with a focus on community-building can help Kasparovchess stand out among competitors such as Chess.com or Carlson-fronted Play Magnus – the parent company of which netted £40m in investment when it floated on the Norwegian stock exchange last year.

Community-building will be within an “interactive context”, he says, using its dedicated Discord group-chat platform and leaning heavily on grandmaster ambassadors to draw a crowd. Audiences, he notes, have become used to direct access to esports personalities. “This is why Twitch is popular these days, because it’s spontaneous... it’s a very important way of communicating with new audiences, especially younger audiences.”

In that spirit, Kasparov plans to offer up his brains for picking by chess fans, providing “quote-unquote spontaneous content” in the form of advice and analysis. He has also recorded an exclusive tutorial for the site, offering members the chance to learn directly from the master.

Global lockdowns provoked even more people to pick up their chess boards and apps, and Kasparov hopes his timing and his strategy of combining learning and playing will seize the moment.

“There’s so many people who discovered chess recently and many others who knew how to play but didn’t because they were too busy, always with other things to do. If you can drag them in and you can make them excited, if you offer them this element of entertainment through education and learning, we can dramatically expand the global chess audience.

“I’m no longer a professional player, but I know how to sell the game. And I know how to bring people in because, again, it’s all about excitement. We have to get people excited about the game and what the game can offer.”