Inside Adform’s ‘Hyphbot’ ad fraud takedown

The Drum talks with Jay Stevens, Adform’s chief revenue officer, on how his team called out what it claims is the worst instance of ad fraud on record, how to prevent falling victim to such activity, as well as starving bad actors of income.

Last week, the exposure of allegedly one of the biggest bot networks ever to be discovered underlined the looming threat that ad fraud poses to the digital media sector.

Adform, the adtech outfit behind the revelation, claims the bot network – dubbed “Hyphbot” – was so sophisticated that it compromised up to 500,000 machines, and generated up to a 1.5 billion fake ad requests a day.

First detected in September, the perpetrators behind the fraudulent operation generated a wave of fake websites designed to mimic the behavior of human traffic, as well as spoof ad exchanges and advertisers that its fake URLs were premium web properties.

In fact, so endemic was its scale that experts have estimated that it was four-times the size of the Methbot operation, which generated acres of coverage in mainstream media 12 months ago.

Assessing the scale of its financial impact is still difficult, but Adform estimates that this could run into in excess of $500,000 a day, a figure so concerning that law enforcement is looking into the findings, according to reports.

The ‘real deal’ this time?

Comparisons with Methbot are somewhat controversial, given that the scale of its impact first reported by WhiteOps, which claimed that this bot network siphoned off up to $5m a day from the industry, has since been widely disputed.

So judicious was Adform in broaching this matter, that leadership of the company sought the counsel of renowned auditor Shailin Dhar founder of Method Media Intelligence, as well as prominent adtech expert Dr Neal Richter, chief technology officer at Rakuten Marketing, and one of the architects of the ads.txt initiative.

Jay Stevens, Adform, chief revenue officer, explains how this peer-review approach helped validate his company’s earliest concerns, as well as how the ensuing publicity has helped galvanize the industry's fight against ad fraud.

Hyphbot fraudsters used guerrilla tactics, not sustained attacks

Based on the number of infected cookies and the IP addresses, Adform estimates that over half a million machines were compromised by Hyphbot, this is compared to more orthodox bot networks which usually operate out of data centers.

According to Stevens, Hyphbot's means of operation makes detection more difficult, because the more widespread the bot network is distributed, the less pronounced are the signs of fraudulent activity. So whereas Methbot’s fraudulent activity primarily took place via compromised data centers, Hyphbot's predominantly took place on individual machines.

“The difference is like Napster versus Kazaa – and Kazaa being a more distributed system, rather than Napster which was all on central servers,” explains Stevens, comparing the havoc wrought by the respective bot networks to the tactics (and disruption) of the early file sharing sites of the dot com era.

This made Hyphbot's perpatrators more adept at evading the detection techniques employed by many of the industry’s anti-fraud systems. This is because the nefarious activity was more akin to guerrilla warfare, as opposed to more sustained attacks, which then raise red flags of most security systems on the market.

For instance, a classic tell-tale sign of ad fraud is if a handful of IP addresses generate an inordinate amount of traffic, then even the most rudimentary anti-fraud software system will alert the responsible team to delve further. But Hyphbot simply didn't operate in such a manner.

How Hyphbot was red-flagged

Hyphbot infected individuals’ machines by gaining access to their desktops, doing so by ‘taking over the machines’ of users that inadvertently download malicious software plug-ins, or other means, and then instigating user sessions without their knowledge.

“The other thing about this and MethBot, is that MethBot was using its own browser whereas this [Hyphbot] was using Chrome,” adds Stevens, further indicating the levels of sophistication employed by the latest fraudsters.

It was whenever a series of “odd URLs”, such as those designed to fool automated systems by being coded and tagged to resemble premium domains, kept recurring in Adform’s log-files, that the company’s team figured this “didn’t make any sense” and prompted them to look further. "Obviously, once we started to drill down into these, we stopped buying any of that traffic, except for research purposes,” explains Stevens.

Flushing out the fraudsters

During this research period, Adform began buying sample amounts of traffic in an attempt to establish the scale and source of the fraudulent activity; an activity it undertook by injecting their own source code into the campaign creative of said impressions.

“Because our ad server and DSP [demand-side platform] are linked – whereas most DSPs are just buying media, and not delivering it – then we were able to inject script into the code of the creative and dig quite a bit deeper,” explains Stevens.

From there, it was able to get closer to the source of the issue, and establish protocols to prevent further losses to such fraudsters.

“The reason we decided to blow the lid of it was to share the findings with the marketplaces so they can implement similar pattern recognition into their products and help stamp it out,” explains Stevens.

A call to arms

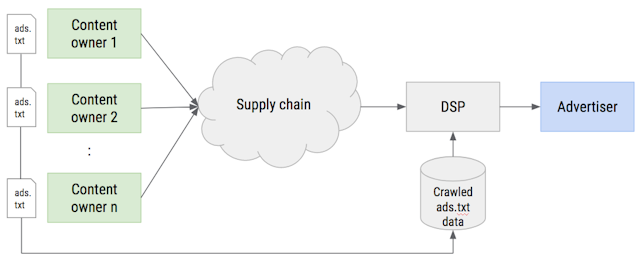

Adform is calling its latest findings – available via a white paper here – a “call to arms” for premium publishers to adopt the ads.txt protocol, an initiative launched earlier this year by the IAB Tech Lab to prevent a means of ad fraud called domain spoofing. This initiative encourages premium publishers to publicly list their authorized resellers of their ad inventory, ergo ostracizing those peddling fake 'lookalike URLs'.

By adopting ads.txt publishers can alert third-party media buyers (including automated buying platforms) that want to source premium media space exactly which inventory sources are legitimately represent them. Simply inputting the script ‘/ads.txt’ after a relevant premium publisehr's URL will display exactly whom such parties are – see more here on how News Corp has implemented ads.txt.

Since launching earlier this year, over 50% of the top ComScore publishers have implemented ads.txt, and many third-party ad exchanges have been keen to trumpet their support of the initiative, including AppNexus, Google, Index Exchange, OpenX, PubMatic and Rubicon Project. This is in addition to adtech players on the buy-side of the industry.

Ads.txt is not a silver bullet

However, ads.txt is “not a silver bullet” according to Stevens, who is keen to point out how even if the initiative is supported by buy-side players, such as his own outfit’s DSP, loopholes that still exist which can be exploited by bad actors.

For instance, even though a premium publisher can implement the new initiative, the presence of just one “dodgy exchange” on an ads.txt file can create a back door for fraudsters.

“Let’s say that an SSP [supply-side platform] has a dodgy ad network that they’re using for back-filing, they can essentially spoof the same domain that the premium publisher has appointed the legitimate SSP to represent its inventory in their exchange,” he explains.

Back doors are still open to fraudsters

Such a dynamic can then result in an instance where a buyer searching for premium inventory in an ad exchange could be ‘spoofed’; as it sees what appears to be same URL twice in the same ‘trusted’ environment.

Given that many media traders are incentivized to optimize their buying strategies towards keeping costs low – a bugbear of some of the ‘godfathers of adtech’ – there is a strong likelihood such a buyer will opt for the cheaper, ergo fake, impression. In such an instance, all legitimate players lose out.

This demonstrates how publishers need to conduct a thorough audit of their adtech supply chain can lead, and not simply resting on the laurels of ads.txt implementation, in order to stay ahead of fraudsters, according to Stevens.

“Premium publishers, like the FT are hyper-sensitive to this and they only have two trusted exchanges they allow [to resell their inventory]," he says.

“But then you go to other premium publishers [look through their ads.txt file] and it’s like a whole laundry list of every SSP and their brother, and their dog, that’s allowed to sell their inventory."

Stevens goes on to warn: “So if one of those exchanges doesn’t have the strict regulations about how they onboard inventory, and the kinds of people they work with, then that creates an avenue for fraud to continue to exist.

“Publishers still have to be extremely vigilant about who they work with, and that’s a key takeaway.”

Stevens advises those in the ecosystem to pursue direct relationships with publishers, and to be wary of supply chain partners that have “backfill relationships.” Similar to how those in the financial services industry must ensure equities sold on their exchanges are legitimate, it is incumbent on ad exchanges to perform such checks. “It’s a very similar analogy,” he adds.

How fraudsters siphon money away from the legitimate ecosystem

Experts have forecast that ad fraud will cost the advertising ecosystem as much as $50bn per year by 2025, and state that this is a source of revenue second only to dealing in narcotics for major organized crime elements.

The complicated nature of the adtech supply chain, plus the confusion inherent in all high frequency trading environments has been used by bad actors to obscure their nefarious activity, and thus siphon money out of the online advertising ecosystem.

Stevens draws on his 10 years-plus experience in such environments to demonstrate how this complex ecosystem has historically played into the hands of fraudsters, and also offers his take on how to turn-off such sources of income.

“Let’s say you’re a dodgy ad network and spoofing URLs, you then go to an SSP or exchange and have them back-fill your inventory [ie sell it on your behalf]. The money then goes from an advertiser to a DSP, from the DSP to an SSP, and then to said network,” he explains.

However, if an ad exchange spots activity that suggests fraudulent activity, then it is in a position to withhold payment to said bad actors, according to Stevens, who implores the wider industry to implement the protocols recommended in his company’s recent white paper.

Law enforcement is taking an ever growing look at ad fraud

Since its discovery, Adform has implemented a series of protocols to better recognize such sophisticated levels of fraudulent activity, and subsequently handed its findings over to the FBI and Metropolitan Police in the UK.

It is still unclear if the players behind Hyphbot have ceased their operations, or whether or not how the FBI will act upon Adform's recent findings. Although, the US agency it is understood to be taking an ever increasing interest in such fraudulent activity. Agents from the bureau were reported to have been trawling the corridors of relevant adtech trade fairs for intelligence earlier in the year, and well placed sources (speaking upon condition of anonymity) inform The Drum that indictments are on the way.

Of course, the tactics of using shell companies to transfer any monies generated by such activity make it difficult to shine a light on any paper trail necessary to secure convictions, but bringing such parties to justice is not without precedent.

Earlier this year, a Federal court in Brooklyn, New York, passed sentence on cybercriminal Fabio Gasperini, an Italian citizen, for compromising both servers and individual’s computers to generate fake traffic and defraud advertisers of money. This was made possible following an FBI investigation in cooperation with international authorities which resulted Gasperini’s arrest, extradition and subsequent conviction.

Given the emphasis on cleaning up the murkier elements of the online media ecosystem in the current media climate, it would suggest that the appetite and technological possibilities exist for such convictions to be repeated.